Icarus shot for the sun, of course; F1 aerodynamics perform precisely the opposite function, using the science of airflow to push everything down towards the track. This ‘downforce’ – which can be in excess of 2000kg pressing a car into the racetrack – has the effect of vastly increasing the amount of grip produced by a chassis, with a commensurate increase in cornering speeds.

By way of example, F1’s fastest corner – Copse at Silverstone – is expected to be taken at more than 180mph during this year’s British Grand Prix, loading drivers with a cornering force five times their body weight. These speeds and loads are partly a function of power: the turbo-hybrid motors of current-gen F1 cars produce the equivalent of around 950bhp. But the cornering speeds are dictated largely by the grip available; and the story of that grip starts at the very tip of the car, with those intricate, delicate, hugely expensive but staggeringly effective front wings, crafted from carbon fiber.

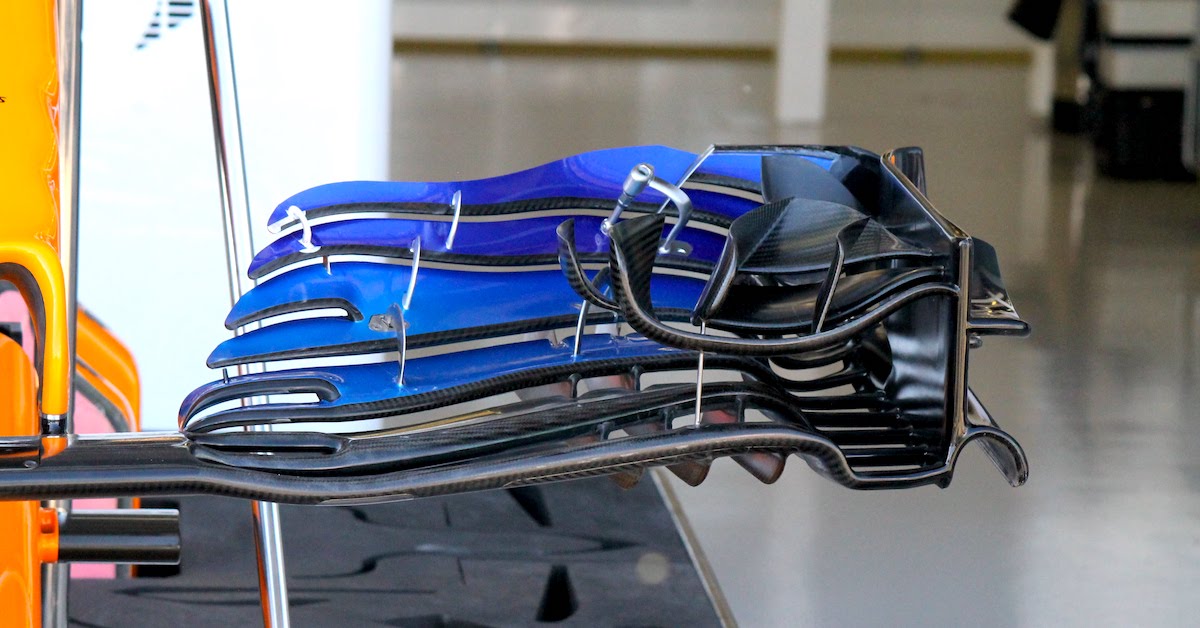

Their form, which seems more organic than man-made, such is their inter-layered detail, is the result of hundreds of thousands of hours’ aerodynamic research in both wind tunnels and with computational fluid dynamics (CFD) modeling, within a framework governed by the F1 technical regulations.

Accordingly, a front wing must be no more than 1800mm wide, nor can it exceed 275mm in height, when measured from a lower reference plane. Then there is the so-called ‘Y250’ zone – a central section of wing measuring 250mm either side of the car’s centerline – which must be aerodynamically neutral. From these stipulations have grown the elaborate multi-element components that serve two key functions: (i) to generate downforce; (ii) to shape and channel airflow behind the front wing in such a way that all the car’s other surfaces – rear wing, engine cover, air intake, radiator pods, underfloor, diffuser – can function in the most aerodynamically efficient manner possible, i.e. by generating maximum downforce, while incurring minimum drag.

Over the F1 decades, the front wing has evolved from being little more than a relatively simple ‘flap’ that reduced a car’s tendency to lift from the ground at high speed, into the single most important element of the almost infinitely complex aerodynamic tapestry of an F1 car.

The wing’s so-called ‘cascades’ – the tiered leaf-like structures at its extremities – act to generate vortices behind them that spiral upwards and outwards in channels controlled to the millimeter and shaped around the front wheels; towards the underfloor; through and around radiator inlets and between suspension components.

To the naked eye this airflow manipulation is invisible: only in wet conditions is there obvious evidence of the aerodynamic disruption caused by a speeding F1 car – those huge ‘rooster tails’ of spray thrown up as they pass. And to the casual observer, the front wing may seem little more than a complex-looking extrusion prone to being shattered into carbon shards whenever F1 drivers play ‘bumper cars’.

But that’s to do them a shameful disservice. They’re among the most sophisticated Formula 1 components ever devised and without them its incredible cornering speeds would quickly fall to earth.

Earlier this week the FIA announced aerodynamic regulation changes for the 2019 F1 season intended to promote close racing and more overtaking. Among the proposed changes is a “simplified font wing, with a larger span, and low outwash potential.” Will the 2018 front wing be remembered as the most advanced in Formula 1 history? Time will tell.

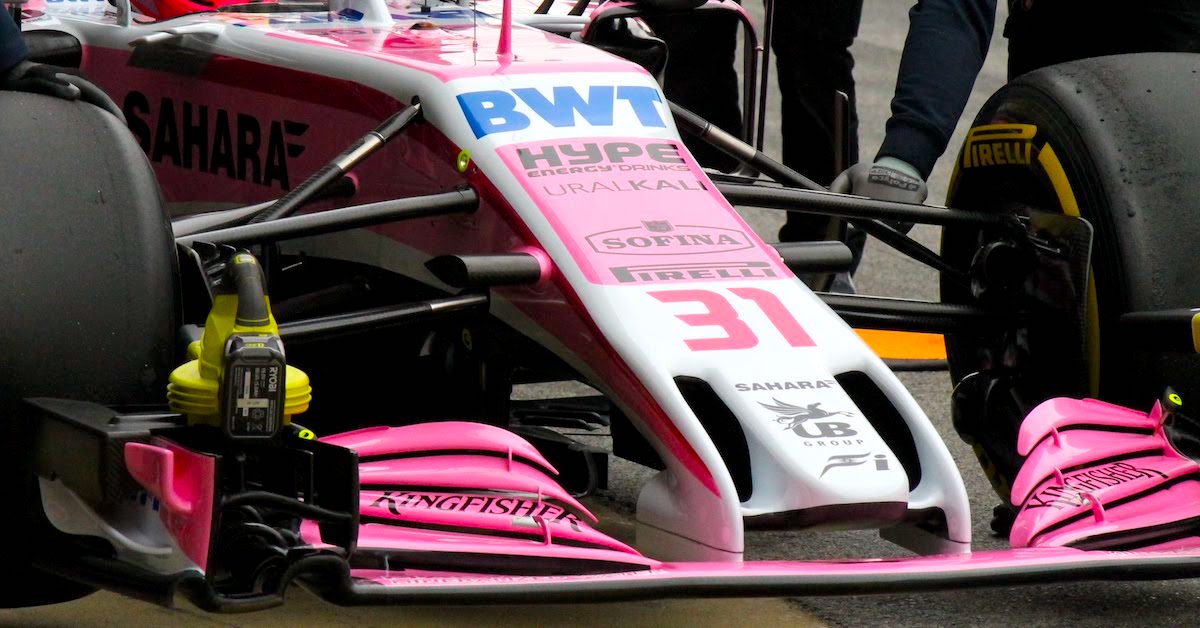

Top Image: Williams Martini Racing FW41 nose cone and front wings at the Formula 1 2018 Australian Grand Prix. © Acronis.

F1 teams trialed 2019-spec front wings during Hungary test days. Here is a great gallery of 2019 F1 wings prototypes: https://www.formula1.com/en/latest/headlines/2018/7/f1-2019-front-wing-designs-make-debut-in-hungary-testing.html

2018 Front wings should have a place at the Tate Modern ,but let’s hope for better racing in 2019 right on the gearbox of the car in front proper slipstreaming fingers crossed .