Perfect planning is a cornerstone of F1 operations. Everything is pre-planned and scheduled ahead of the weekend to the nth degree. There’s a well-worn routine for the teams operating at the track, everything has been thought of. But there come situations when even perfect planning goes awry and something out of the blue happens. When one of your race cars is damaged beyond repair at the track, how do you still go racing? How do you rebuild a car in the pit garage?

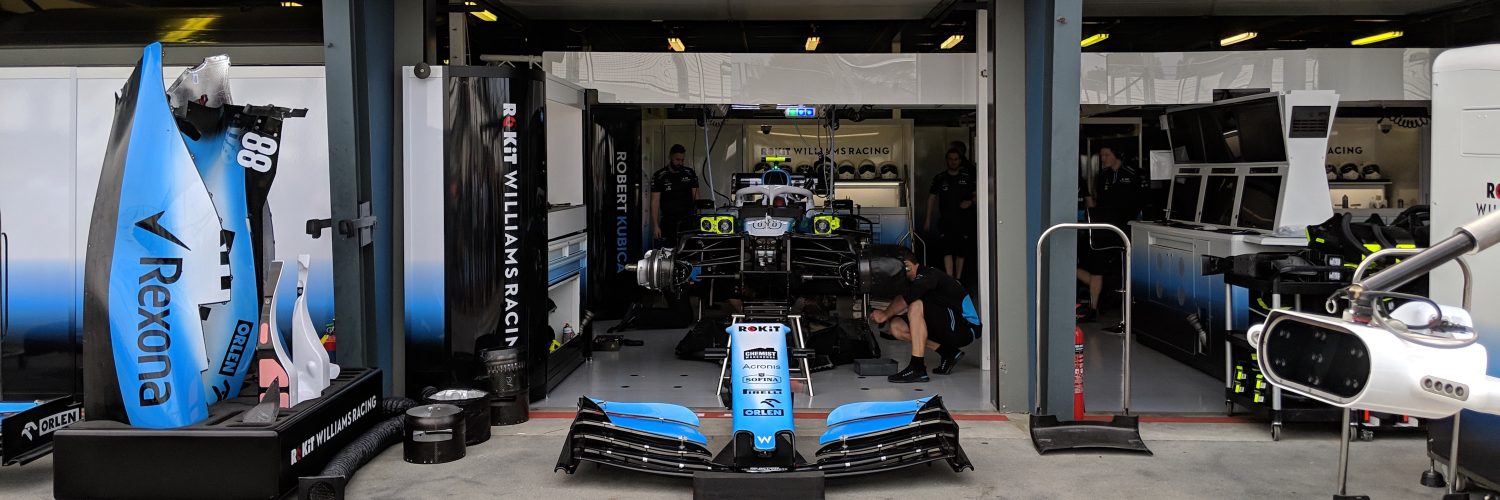

When George Russell ran into a loose drain cover during the first free practice session in his Williams in Baku, the resulting damage meant that Williams had a long day ahead of them. F1 is a 24-hour operation, but in recent times the work at the track has been cut back. The FIA have enforced a curfew for the mechanics, so the days of burning the midnight oil through Friday and Saturday nights are largely over. But, there always comes a time when long hours are required.

If this were sixteen years ago, this wouldn’t have been a problem. Russell would have jumped into the spare car and continued his run-schedule according to plan. Up until 2003, spare cars were allowed and every team had a complete car sat in the garage waiting for use. This car would be set up for one driver, allowing that driver to flit between cars during practice. Or the second driver could use it, if trouble occurred, once the pedals, steering wheel, seat and race numbers were swapped over. Without a spare car allowed, teams now bring a spare monocoque and enough parts to build it into a complete car if necessary.

Subsequently, other rules were introduced to cut the workload for the mechanics and costs, such as Parc Fermé, where the car as it finished qualifying must go into the race unchanged. Before this, teams were completely rebuilding the cars between qualifying and the race; aero set up, engines, gearboxes, brakes and other light weight parts were all changed to have the best car for Saturday and Sunday afternoons. With this rule change came the curfew, enforcing an early finish each evening and a reasonable start time in the morning. There is a get-out clause – the teams have ‘jokers’ where they can work late or start early, plus in some cases the FIA can grant an extension for team to recover from situations out of their control.

With the obvious major damage to the Williams in Baku, the race monocoque used by Russell was beyond repair and thus he needed the spare tub to be built up ready for Saturday. Due to the circumstances, the FIA granted a break in the curfew to get the rebuild completed. Building up a new car from a spare monocoque at the track is not unheard of, but quite rare nowadays. Neither is this a unique job for the mechanics, in between races the car is stripped to have parts inspected, changed or upgraded. At flyaway races, the car must be broken down to fit in the flight containers to be flown to the next race. This sort of work is scheduled, and the mechanics are well versed in rebuilding the car. When there is a mid-weekend rebuild, the clock is ticking, there is a huge amount of work to do while sessions continue outside the confines of the pit garage. For Williams in Azerbaijan, this work started after free practice 1 and will go on in late into the night.

What goes into building up a car from a bare shell?

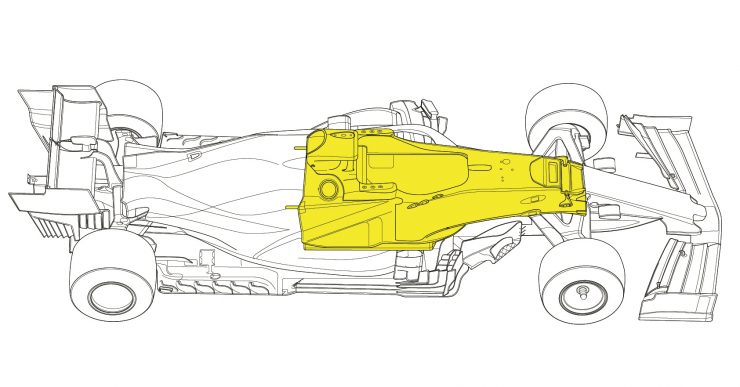

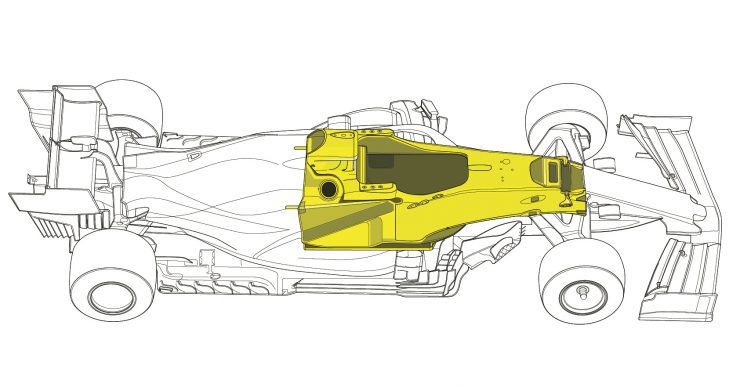

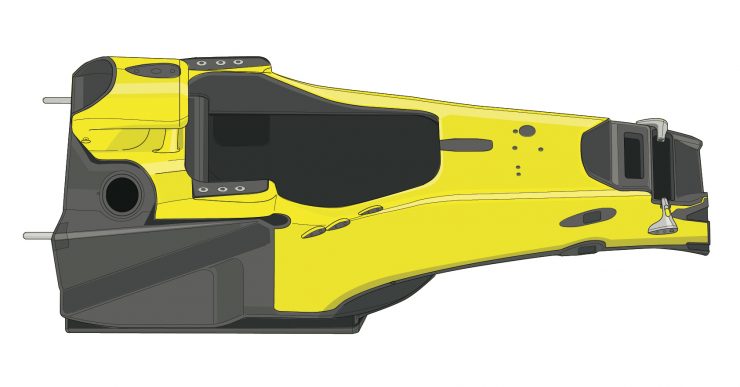

Firstly, let’s look at the monocoque. This is what the FIA calls the driver survival cell and is the key structure around the driver for protection in the event of an accident. But, of course, the survival cell does far more than just house the driver. The monocoque is at the core of the car, it forms the basic structure of the car, everything is bolted to it to make the car go.

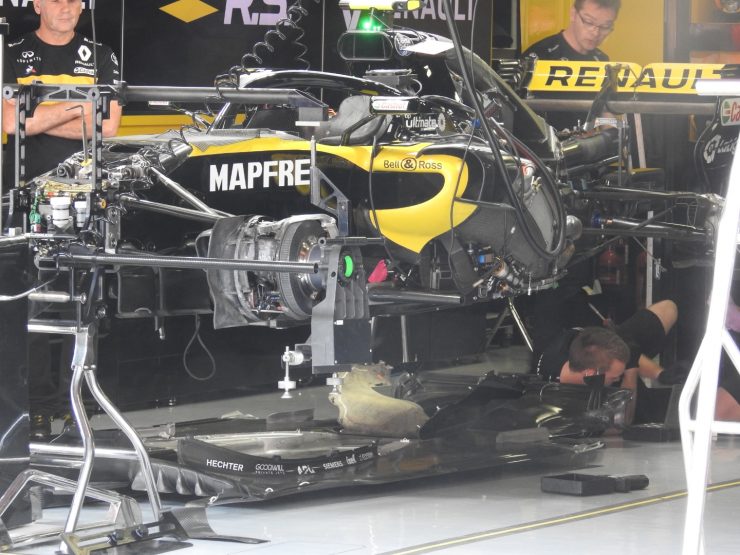

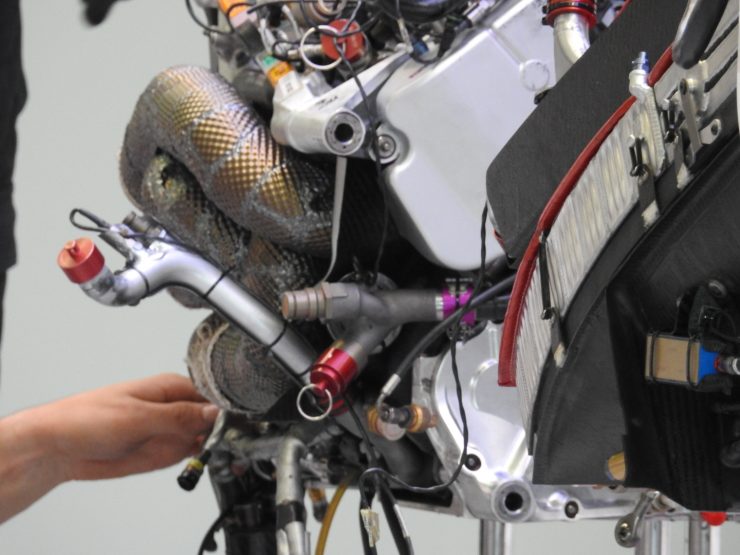

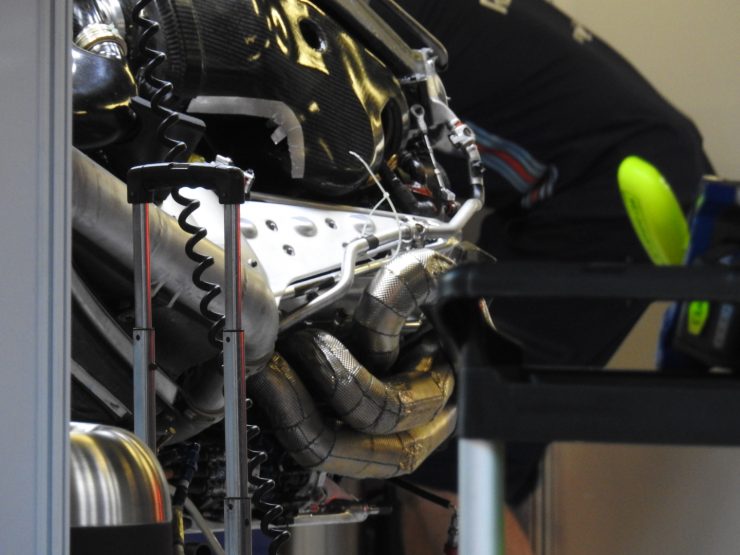

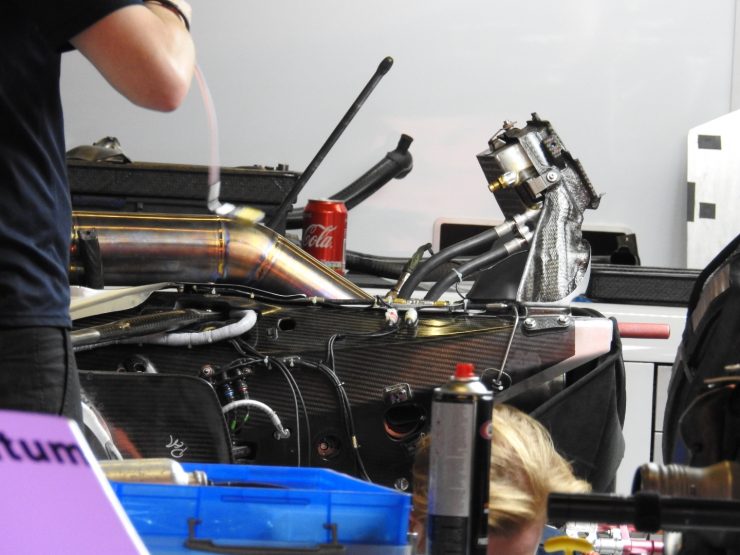

So, nearly all of the 11,000 parts that go into the chassis need to be fitted. Luckily not individually, but mainly as pre-constructed assemblies; suspension, fuel tank, engine, radiators, electronics or bodywork. Everything either directly or in turn gets bolted to it, making the monocoque effectively a giant bracket! This factor makes a rushed rebuild harder as everything needs to go from the old car or from the spares drawers onto the new tub.

To make this easier, the spare tub is already set up ready for some of the rebuild, as some tasks need time and space to complete and are not suited to rebuilds in the field. To start with, the monocoque is fully legal having been crash tested and painted ready for the parts to be fitted. Also, the fuel tank and its internal collectors and pumps will be readied, as the task of squeezing the flexible bag tank through the tiny hatch in the monocoque floor is one best done with time and space along with the special tooling that guides it in. Equally, the laborious task of fitting the main wiring loom, break out boxes and some sensors will be completed. Likewise, the pipe work for brakes and hydraulic steering rack will be in situ. Some of the suspension internals will be fitted too – the front rockers that operate the springs and dampers via the pushrod sit in bearings will be pre-fitted. So, it’s not unusual to see a spare tub, with the metal tops of the pushrods dangling from the top of the chassis, waiting for the rest of the suspension to be fitted. Once taken from its shipping container, the spare tub will be set up on trestles in the garage and ready for its rebuild.

Parts fitted to the new tub will depend on the reason for the rebuild. More often than not, this will be due to crash damage, so some parts will not be reused. At this point, the cause of the accident will be a big factor. Was it driver error or circumstances beyond the team’s control, Force Majeure? Perhaps the crash was caused by a part failure? If that’s ever the case then the team need to establish the root cause and consider if identical parts would be a risk if fitted to the car, or perhaps have modified parts prepared for the rebuild to prevent a reoccurrence of the failure.

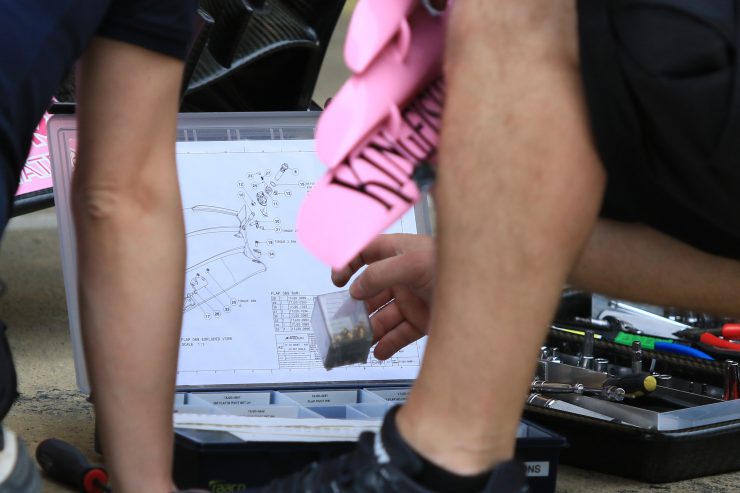

Equally, to get the rebuild going quicker, it might be easier to fit new spares, rather than wait for the old parts to come off the damaged car. Otherwise, it’s the long task of taking parts from the damaged car and moving them over to the new car. There’ll be a well-practiced sequence to do this, honed from years of inter-race rebuilds. While the mechanics will know the car inside and out, there are both paper and electronic aids to confirm the assembly of parts. Not quite an owner’s manual, but pages of schematics and assemblies, with annotations regarding how the parts are fitted, what bonding agents and torque settings to use.

With the major parts installed, the detailed work of clicking in the wiring connectors, attaching fluid lines and bleeding them id done. Finally, the car may be ready for its first fire up, but the job is not complete with this. Once the car is technically proven to be working, the set up then must be dialled into the car – suspension geometry, damper/spring settings and wing angles etc. Only then can the car turn a wheel, but will only complete an out lap, then go back into the pits for partial strip down to ensure there are no leaks or loose parts and to correct any issues detected from the first lap.

Only after this long, detailed process can the car go out in anger and once again set some lap times.