When McLaren announced this week that 18-year-old hot shoe Lando Norris would be replacing Stoffel Vandoorne at the team for the 2019 season, it raised no shortage of eyebrows.

Norris currently lies second in the Formula 2 series and boasts an impressive junior record of racing in seven different categories and winning three of these, including the prestigious Formula Three Euroseries last year.

Added to this is the fact that he joined McLaren as a development driver in 2017 and is the team’s test and reserve driver, having driven in practice in both Belgium and Italy. So, it should come as no surprise whatsoever that he has landed his big break.

Indeed, this kind of promotion from the ranks of the leading feeder series to the pinnacle of motorsport is nothing new. The man he is set to replace had arguably as impressive a junior career but has failed to make an impression in an often-uncompetitive machine and against a yardstick in Fernando Alonso who is one of the greats of the sport.

The likes of highly-rated Ferrari target Charles Leclerc and Acronis-backed team drivers Esteban Ocon, Sergey Sirotkin and Lance Stroll have all trodden the well-worn path into the big time.

So why do some drivers succeed whereas other fall flat and just how big a step up is it from F2 to F1 and how different are the cars to drive?

Of course, the most obvious and noticeable difference you will hear from young drivers after they step into an F1 car for the first time is the sheer scale of the power difference in terms of acceleration, top-line speed and braking.

— Lando Norris (@LandoNorris) September 4, 2018

“Jumping from F2 is still a fairly large step, and it does take a bit of time to get used to it,” Norris said after his first taste of testing the McLaren in 2017. “There are definitely things we need to improve and work on, but the car is still very good to drive. It does give me a lot of confidence to carry the throttle and I don’t think I’m on the limit yet.”

Interestingly, his fastest time set on soft compound tyres around the Circuit de Catalunya Barcelona this year bettered both of Vandoorne’s during qualifying at the same circuit on the supersoft and soft tyres.

Unlike in F1, all 20 cars on the F2 grid are identical in their Dallara chassis and Mecachrome engine, so this gives fans a real gauge of exactly who the best drivers really are. Norris clearly fits into that bracket.

The 2018 iteration of the F2 machine now has a V6 turbo and it’s the first time that this has been integrated to F2 cars as opposed to normally aspirated powerplants used in previous seasons. The car has the same kind of look and feel to that of an F1 car and features a 3.4 liter power plant.

It means that the cars are now much faster than they were in 2017, when they were often over ten seconds per lap slower than their F1 counterparts, even on the higher downforce circuits such as Monaco and Hungary. Monza F2 race winner George Russell topped the speed trap at 217mph this year with a fastest lap of 1m34.899 in comparison to compatriot Lewis Hamilton’s 1m22.497 on one of the fastest of circuits in the world. It’s not quite like you or I stepping into, say, a Mini Cooper to a Porsche 911 GT3 in terms of performance, but a big step up nonetheless.

And yet there are some closer similarities that may give Norris that extra edge when when he lines up on the grid in Melbourne. Drivers in the F2 series now have the added benefit of learning how to manage their tyre wear, just like their F1 counterparts, with the Pirelli tyres facing the same kind of degradation although the range of compounds is limited to only two.

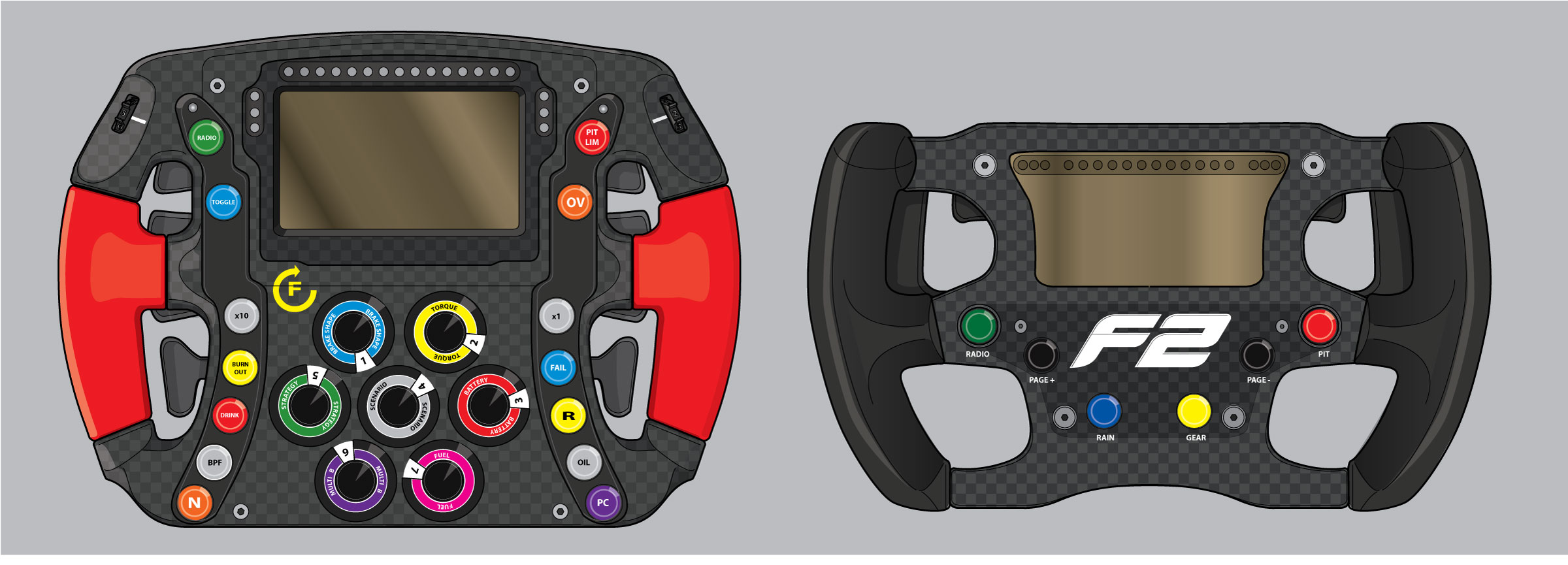

Perhaps one of the hardest things for Norris to get to grips with, as he explains in this excellent McLaren YouTube video, is the myriad controls and buttons a driver must master on the F1 wheel.

As you can also see by this excellent Craig Scarborough illustration below, the job of driving an F2 car is quite uncomplicated in comparison. Whereas the job of an F2 driver is primarily focused on the purest aspects of driving, the modern-day F1 pilot must seemingly have the skills of a NASA astronaut in terms of decision making and juggling cockpit instrumentation.

Like their big F1 brothers, F2 cars now also feature the Drag Reduction System (DRS) to aid overtaking and drivers are also used to the now mandatory Halo safety feature around the cockpit. Despite these small similarities, it is well worth remembering that the engineering budgets between the two series are worlds apart. The entire Dallara car, minus the engine, costs around $300,000 – approximately the price of just the floor component of its F1 counterpart!

The final variable that drivers must adjust to is the added stresses and strains that an F1 car exerts on the body. The G-forces of cornering are similar (up to 3.6g) but the race distances and the season far longer than in F2.

With 21 races on the calendar as opposed to 11 in F2, Norris will experience some extremes that will be new to him. This includes circuits such as Singapore, where he can expect to lose up to three kilos of fluid in 30-degree heat and 70 per cent Tropical humidity and other circuits that present new and different challenges.

Norris has the advantage of youth on his side and will have the very best physical trainers and dieticians available to him to ensure he is totally match fit when the new season kicks off in Melbourne on March 17.

All this considered, just how do we expect Lando to fare in 2018 when paired up with his more experienced teammate, the highly-rated Carlos Sainz?

As always, making predictions in the complicated world of Formula 1 would be foolish indeed. It can depend on so many variables including engine power, aerodynamic package and, of course, that magic sprinkling of luck. Having a competitive car underneath him will make things that much easier although his ultimate yardstick will be his teammate.

What is for certain is that Norris has already proven himself amongst the very best when the playing field is a level one and has been given the best possible apprenticeship of the McLaren young driver development programme.

Yet even that does not guarantee success in the toughest of motorsport schools. Just ask Stoffel Vandoorne.

How Lando Norris’s McLaren F1 and Carlin F2 machines compare:

McLaren Renault MCL33 (McLaren official site)

Weight: 733kg (including driver, excluding fuel) Bodywork: Carbon-fibre composite, including engine cover, sidepods, floor, nose, front wing and rear wing with driver-operated drag reduction system Engine: 1.6 litre, V6 Hybrid Max speed: 15,000 rpm (internal combustion engine), 50,000 rpm MGU-K, 125,000 rpm MGU-H. Gear ratios: Eight forward and one reverse. Steering: Power-assisted rack and pinion Suspension: Carbon-fibre wishbone and pushrod suspension elements operating inboard torsion bar and damper system (F). Carbon-fibre wishbone and pullrod suspension elements operating inboard torsion bar and damper system (R). Brakes: Akebono brake calipers and master cylinders. Akebono ‘brake by wire’ rear brake control system. Carbon discs and pads.

Carlin F2 (Carlin official site)

Weight: 688kg (including driver, excluding fuel). Bodywork: Sandwich Carbon/aluminium honeycomb structure made by Dallara. Engine: 4 litre, V8 single turbo charged Mecachrome engine. Max speed: 10,000 rpm - 328 km/h (Monza aero configuration + DRS) Gear ratios: 6-speed longitudinal sequential gearbox via paddle shift Electro-hydraulic command via paddle shift from steering wheel. Steering: Non-assisted rack and pinion. Suspension: Double steel wishbones, pushrod operated, twin dampers and torsion bars suspension (F) and spring suspension (R). Brakes: 6 pistons monobloc Brembo calliper. Carbon-carbon brake discs and pads.

Top photo: Lando Norris. ©McLaren F1.