An ex-driver TV pundit called F1 “safe enough” only just a couple of years ago, but the question of safety is never ending and taken extremely seriously by the FIA. Every accident, across all categories, provides data to inform the FIA’s safety institute. This went a step further, when the FIA announced this month of a series of new safety initiatives, aimed at addressing issues highlighted in 28 accidents in 2019, sadly including fatal crashes.

The findings from the investigations into these incidents sees the FIA propose a wide range of new developments covering; crash structures, debris containment, warning systems, race direction and track infrastructure.

FIA’s safety approach

The FIA are responsible for the safety of all of its race series, this covers: the car, the driver’s equipment, the trackside features and race direction. To manage this wide ranging discipline, the FIA Foundation has been established, with its job to look at developing new solutions to safeguard everyone involved at a race.

For single seaters, the FIA cascade safety measures, with most sub-categories having a spec chassis, they will take safety advances when the new spec chassis is introduced, dependant on the series budget. So upper level series such as Formula E, F2 and F3 will be almost identical in safety aspects to an F1 car. While the cheaper to operate series follow a little later and may pick and choose with the agreement of the FIA how far some of the more expensive measures are introduced.

Crash Structures

Crash Structures

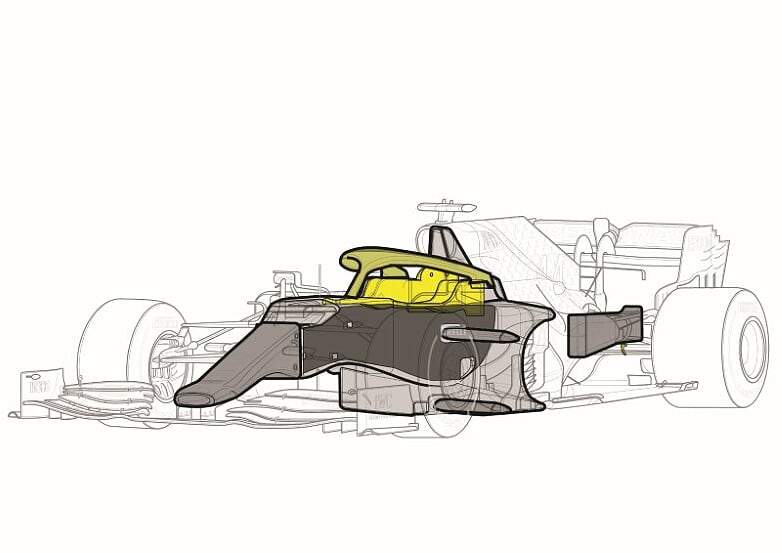

The primary safety defence for the driver are the safety structures built around the car, from the monocoque itself and its roll structures to the front/side/rear impact structures bolted around the car. This survival cell has been upgraded continuously over recent years. With F1’s greater budgets affording each team new car each year, this series tends to spearhead new developments.

Features include greater load and impact testing, anti-intrusion side panels and most recently, HALO. Crash structures and subsequently impact testing has been part of the sign off for every new F1 car for decades. More recently, the demand to bond an Anti-Intrusion Panel to the sides of the monocoque has been introduced.

The composite lay up of the panels with carbon fibre and Xylon help to prevent pointed objects breaking through the monocoque wall during an accident. The HALO Frontal Cockpit Protection (FCP) was negatively received upon its introduction, but has proven itself on the track in protecting the driver from other cars and debris. IndyCar has take a step further with the Red Bull developed ‘Aeroscreen’ and British F3 with the FCP Fin.

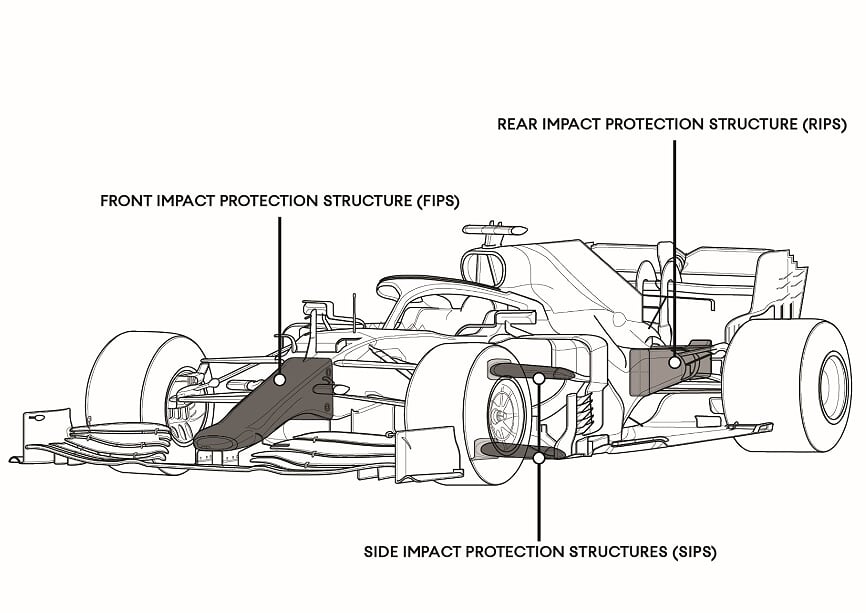

From this solid starting position, recent evidence shows safety weaknesses with car-to-car contact and oblique impacts with barriers. Pointed nose tips and Rear Impact Protection Structure (RIPS) can still penetrate the anti intrusion side panels bonded to the flanks of the monocoque, while the Side Impact Protection Structures (SIPS) are too small to help decelerate the impact. The other case being a long nose going into a trackside barrier at an acute angle does little to reduce the impact and tends to spin the car back away from the barrier, potentially into other cars paths, and perhaps with the Front Impact Protection ripped from the car exposing the driver to risk in a secondary impact.

Thus, the FIA are taking a review of the front and side crash structures to reflect these risks, ensuring that each does a better job of protecting the driver and also that they both complement each other in a crash, in a way that they fail to do at the moment.

This could lead to larger impact structures, Front Impact Protection Structures (FIPS) forming the nose, for example, could have a blunter tip, with a larger cross section. Then the SIPS being a structure encompassing more of the sidepod front, rather than their current design as a thin spar. This way, the SIPS and cockpit sides are better arranged to deflect and decelerate a nose tip spearing the car in a T-bone accident. This all-new SIPS was planned as part of the proposed all-new 2021 F1 rules, but this car design has been pushed back to 2022.

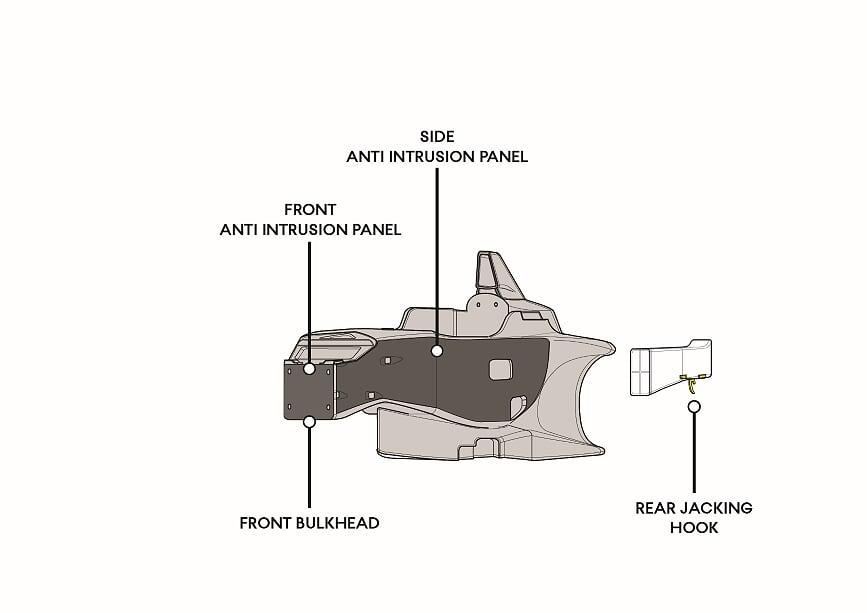

As important as the impact structures is the intention to prevent intrusion into the footwell area during a head on crash, this is in response to the Billy Monger F4 crash. The first change to reduce the risk of injury when a car rear-ends another was the removal of exposed metal rear jacking points. Up until this point the Rear Impact Protection Structure (RIPS) was allowed to have a sharp metal hook attached underneath for the quick lift jack to engage with at pit stops.

It is thought that this part cut through the front bulkhead of Monger’s car, increasing his injuries. The FIA took immediate action to ban this type of jacking hook and F1 responded by the next race in removing all of theirs.

The second change as part of the crash analysis was the front bulkhead, this is the front of the driver’s footwell area, where the nose cone bolts on to. This is commonly moulded as part of the carbon monocoque and has openings to facilitate access to the steering suspension and pedals.

While subject to the FIA crash tests, the intrusion protection of this area of the monocoque hasn’t been regulated and now a FIA specification Front Anti Intrusion Panel (FAIP) must be attached ahead of the front bulkhead to prevent any penetration into the footwell in a frontal crash.

Admirably, British motorsport has already responded with the Tatuus F3 car having a machined from solid FAIP fitted to the car. As with the other impact and anti intrusion developments this will cascade down from F1 to junior single seater categories.

Debris Containment

Part of the process of losing energy from the car in crash is the break up of the cars major components, while a car shedding wheels, bodywork and crash structures is alarming, its part of the process to decelerate the impacts to a survivable level for the driver. However, errant car parts being strewn around the track either from a multiple car pile up or simply a lost front wing from contact during overtaking is a risk in itself.

Even just the break up of carbon bodywork will litter the track with sharp fragments, ready to puncture tyres, is a risk that need further addressing. You will no doubt recall, Felipe Massa’s 2009 Hungary crash was caused by a coil spring falling from another car and hitting his helmet.

Again, the FIA has looked at the problem and now seeks solutions in several areas. Firstly, large sections of car debris being shed from a car, already the wheel assemblies are retained with the car with three up to Xylon tether per wheel. The issue of wheel flying off onto the track or into public enclosure has massively reduced from the post-1994 introduction of wheel tethers.

That, then, leaves the other major structures around the car; wings, nose cones, suspension parts and even powertrain parts. To mitigate or prevent these parts flying around post-accident the FIA is investigating tethering solutions for these parts, as that has been so successful with wheel assemblies.

While the design of the front wing assembly is also being reviewed to see if the wing can fail in a more incremental way, rather than snapping off as the mounting pylons. That way the amount of debris is contained and the driver may retain more control with less downforce lost from the damaged wing.

As regards bodywork fragments, a FIA specification of carbon construction is enforced to the vulnerable front wing endplates. This is now being reviewed, both in the composite construction and the scope of bodywork parts having this construction enforced by regulation.

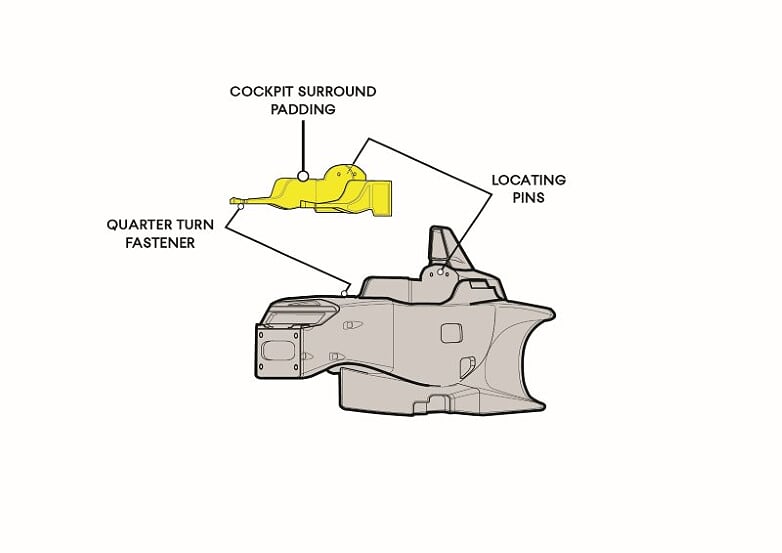

Lastly, the driver’s horseshoe Headrest is being looked at, another post-1994 safety development, the headrest fits to the cockpit opening with two quarter turn fasteners at the front and two pins fitting into recesses in the chassis at the rear. While quick to remove, this is far from a positive and secure mounting for a safety critical component.

This design has had to be upgraded following incidents in F1 where the headrest came loose in crashes and even after being refitted following a race interruption. Again, the FIA’s aim is to look a better means of installation to be both quickly removable and secure in a crash.

Race direction

Cars will always end up off the track over a race weekend, the initial impact is increasingly being dealt with by better on car safety systems, but the fallout from the first impact is often exacerbated by secondary impacts with other cars arriving at the crash scene. Marshals waving flags has always been the primary means to warn drivers, while pit to car radio also helps advise the driver of dangers.

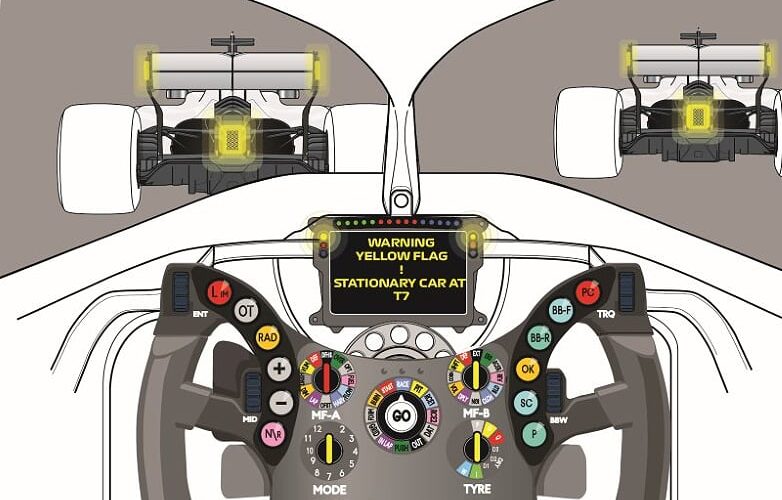

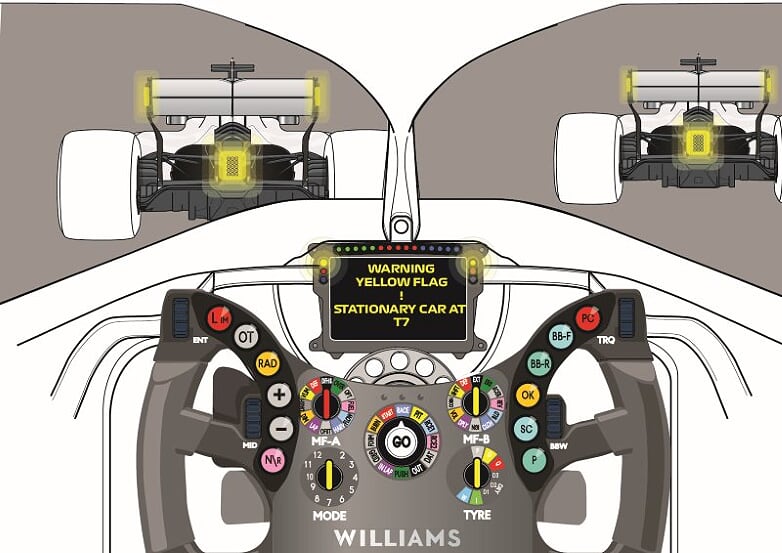

Nowadays, there is the FIA marshalling system that lights up LEDs on the driver’s dashboard corresponding to the flag being waved, and this system will need to trickle down to junior categories while the FIA intend to widen the use and installation for trackside light panels. To ensure that all circuits have a suitable electronic trackside infrastructure in place to alert drivers to incidents on track, the FIA want to use the electronic systems routinely fitted around the track to further forewarn the drivers.

One system may be the rain light fitted to the rear of the cars, this could be integrated into the electronic marshalling system, making the rain light flash yellow. While the driver may miss a flag being waved in the heat of battle, the taillight they are following would not be easy to miss.

Going forwards, more complex in the set up and activation would be systems such as; automated yellow flag generation, direct car-to-car notification of dangerously positioned stationary cars and possibly even the coordinated power reduction or redirection of cars following an incident.

All of these measures would be introduced with measured reaction from the Race Directors to neutralise the race, making the track safer for the drivers, marshals and spectators. It is suggested that best practice guidelines and training materials are updated/created to support Race Directors, particularly in case of incidents at particularly challenging locations on track.

Another simpler and quicker system to employ would be a tyre pressure warning system, advising a driver of a loss in pressure or sudden deflation, helping them prepare for an incident. Most race cars already run Tyre Pressure and Monitoring Systems (TPMS), with the tyre inflation valve linked to a sensor detecting the tyre’s inflation pressure.

F1 teams have run such systems and other tyre deflation warning systems since the 90s. Already, the FIA have acted for F2 and F3 for the 2020 season with just such a system. While it also works to create low cost solution to implement in junior categories.

Trackside safety

Further to the oblique crash angles, the FIA is to conduct new research and testing into acute angle (0-20°) crashes. This should create a new standard of FIA safety barrier to control and absorb the impact of a car glancing a barrier.

One criticism of current track designs is the tarmac run off areas, which prevent the car flipping effect that gravel run off areas can produce, but also lead to what should be high risk overtaking manoeuvres becoming low risk, as the car can rejoin the track after a failed overtaking attempt. A tarmac run off area remains the best for safety, so new high grip surfaces are being researched to help further slow the car before the barriers. To mitigate drivers taking further advantage of this, new solutions for track limit abuses will be looked at in unison.

All of these projects will be researched by the FIA foundation with assistance from the race series, teams and third parties. Some of these initiatives will take years to see a fully developed solution employed at races, following this initial research. Some will be much quicker in getting to the track.

While many an accident will be written of by fans as a freak occurrence or safety improvement being seen by some as a taking a snowflake approach to a what has always been high risk sport. This is strong signal from the FIA that its learning the lessons and is committed to respecting the safety of its drivers, marshals and trackside fans.