As it comes to the winter break, with young driver tests, teams getting new drivers and building new cars, the job of seat fitting becomes an important task. It’s not simply the moulding of a new seat that’s involved, a whole host of small details are part of the process.

These have to take into to account the regulations and the driver’s preferences. This might at first seem a simple engineering task but, as George Russell found as he was fitted for his one off appearance in the Mercedes W11, things aren’t always as easy as that.

F1 cars are prototypes. They are constantly changing and being tailored for each racetrack. So, it is with the cockpit, tailored for each driver, that every detail is pored over to ensure safety and comfort. This process is often the chance for the teams to take photos of their star driver for the first time, as they are fitted to their new car.

For the technical F1 fan, this often allows a rare view of the bare monocoque. Seat fits will show details we rarely get to see. Some are small and unseen, but inconsequential details are similar to all chassis.

In the case of some teams in recent years, the casually snapped photo of a seat fit shown on social media reveals design secrets of the new car that the driver is being fitted in. The last two Mercedes new car seat fit images have shown the side impact protection position, which gave us an insight to planned sidepod inlet design. Last year’s online video of the Bottas W11 seat fit was quickly removed across online platforms, because it revealed too many details that rival teams could perhaps benefit from!

At the heart of the process is the taking of the seat mould, with the driver sitting a bag of foam or beads to form the shape of the seat, later to be made in carbon fibre. Motorsport.tech has covered this in detail before, so this article will deal with the other factors involved. Each team will have its pair of race drivers, plus the reserve and or test drivers, plus a host of simulator and other pilots who need to fit into the car of the monocoque fitted to the simulator. Thus, the seat fit process is well rehearsed and fully documented.

Teams will have a crib sheet of every aspect of the fitting, to ensure nothing is missed and everything is recorded, to be recalled at a later date when setting up the car for a particular driver. Just such a document for the Marussia team back in late 2009 ran to six pages of A4, and no doubt the current top team’s documents go even further.

Throughout F1’s history, there have been massive changes in safety and a lot of them relate to the driver’s seated position within the car. From the early non-existent regulatory demands to detailed positions set out in the current rule book. These rules set out the cockpit’s vital dimensions and geometrical relationships between the driver’s head, hands and feet relative to the car’s safety structures.

Progress has been made to make the cockpit sized to suit most drivers, after a spell in the nineties that narrowed the cockpit seating area and footwell to the point the drivers were too cramped to drive comfortably, nor able to escape the car quickly enough in an emergency.

Even so, some drivers are taller than others, and the 6ft Russell had to squeeze into a racing boots one down from his normal shoe size in order to be comfortable with the Mercedes for race weekend – more of which later.

Once the legal aspects of the driver’s position are met, its down to their preference for the positions of the driving controls, padding and space to move about in. While these requests may be described as comfort factors, its perhaps better to describe them as performance related, as pure comfort is not a primary requirement to operate the car at 100%.

LEGALITY FACTORS

The first aspect of the seat fitting is to arrange the driver in a legal position within the car. Several rules have evolved around these requirements over the years.

The first, and most obvious, is the drivers helmet and hand position relative to the roll structures. For many years, the helmet has had to sit 70mm below an imaginary line from the rear roll hoop to the top of the front rollover structure at the front of the cockpit. Within this envelope, the drivers head can be higher or lower, by moving the position fore and aft under the imaginary line.

Next, the steering wheel and hand position also have to sit 50mm below the roll hoop line with a further demand for the steering wheel to sit below the front hoop of the halo. But given the general position of the driver gripping the steering wheel, these aren’t targets that struggle to be met.

Deep inside the footwell area, another regulation demands the driver’s feet are behind the front axle line, even when the pedals are fully depressed. This rule dates back to the late eighties, when the demand for a rearward driving position was introduced to improve crash protection, as previously the driver’s feet could even be ahead of the front tyres!

Helping the driver fit the car to meet these demands are a series of dimension regulations for the cockpit size. Firstly, the cockpit opening is a regulation shape and height, this extends to the cockpit surround padding and the HALO position. Then as the monocoque reaches forwards to form the footwell area, the cross sections at the dash bulkhead and front bulkhead (where the nose cone attaches) and the distances between them are defined. These are all detailed within the technical regulations and are largely unchanged since they were introduced in the mid-nineties, as part of the FIA post Senna accident Safety Working Group’s activities.

PERFORMANCE FACTORS

With the safety requirements for a seat fitting uncompromisable, the other factors are all about allowing the driver to work to their best ability inside the cockpit. Despite what appears to be a tiny and un-ergonomic cockpit shape, the seated position is surprisingly spacious and arranged well to allow the driver to operate the wheel and pedals.

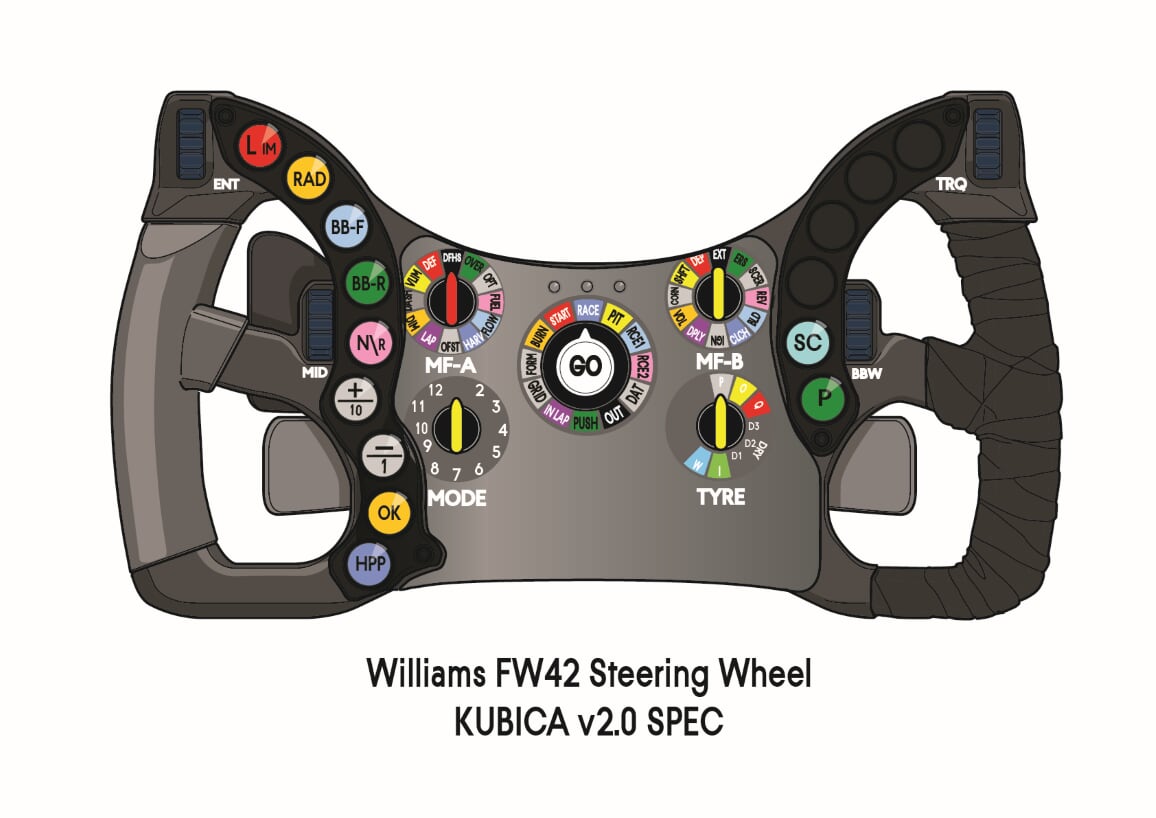

How this works for each driver will vary, depending on their seniority within the team. The race drivers, especially if there is a ‘star’ driver, can have virtually anything they want, whilst junior, academy and simulator drivers will have to work from baseline settings and parts tailored for the race drivers, with less flexibility for one off adaptations. Although every situation is different, as the modifications for a driver such as Robert Kubica showed at Williams, and as a reserve driver at Alfa Romeo.

It will also vary as to what the driver sits in for a seat fitting. The current race car is the best venue, as this will have every detail in place for when the driver gets to run the actual car. Often done pre-season, this will be a mock-up chassis, made from machined moulding block, 3D printed sections and even wood! As this mock-up tub is used to pre-fit all parts of the new car.

It’s a good compromise and, as it remains at the factory through out the year, makes it convenient for junior drivers to visit the team and to have a representative seat fit. But as the FIA rules have been so stable, the basic cockpit dimensions of even a car a few years old will allow an effective seat fit to be conducted.

The precise seated position allows the driver to see clearly out of the cockpit and reach the controls as defined, as long as they do not compromise the safety regulations. Engineers will want the driver to sit lower, to improve airflow to the roll hoop inlet and lower the car’s centre of gravity height. The driver will want to compromise, with a position to see the front wheels clearly to position the car at a corner’s apex.

By locating the helmet’s position, the resulting inclined seated position also defines where the driver’s shoulders, elbows and bottom lie within the cockpit. The steering wheel position is also customisable within a small window regards height, with different column mounting brackets and reach with extra steering wheel spacers. Thereafter, every aspect of the steering wheel can be customised, within the team’s standard wheel design.

Aspects such as button functions, paddle positions, display brightness, hand grip shape can all be played with. Even the knuckle clearance to the cockpit surround padding can be tailored, the aerodynamicists wanting it as closed as possible, while the driver may want more space around the back of their hands as they turn the wheel to full lock.

At Williams, Russell and Latifi are used to a fixed display, but the standard is for it to be on the wheel itself, to not only aid visibility of the dash when turning but also to easily replace the wheel should a fault cause the display to malfunction.

The resulting seating position may have issues with clearance around interior of the moulded carbon fibre monocoque. Years of design refinement at each team eases any major issues so that a driver’s bottom can’t slide forward enough without hitting the heel of the monocoque. A comparatively wide cockpit as it meets the fuel tank bulkhead also creates elbow room for steering.

Also within the cockpit are various pieces of hardware – electronic boxes, extinguisher bottle, drinks system and even gas bottles for the engine’s valve system. These will all need to be distributed around the remaining cockpit space, with consideration to heat being directed towards the driver’s seat. Where this becomes unavoidable, it may require gold or silver heat reflective coatings being added to the back of the driver seat, to keep them cool. Regardless, padding and detail changes may be required and are documented in the seat fit notes.

With the driver placed in the cockpit, the seatbelt anchor points can be confirmed. Teams will have several positions for the belts to be bolted to, to suit different driver heights – as well as the lengths of each of the six straps and buckle position being tailored around the driver’s torso and HANS neck collar.

Then it’s onto the pedals. Teams will have their own standard pedal design, which evolves slowly over time. The pedal position can be tailored fore and aft, as well as spacers fitted between the pedal and pedal face, for finer adjustment. More intricately, the driver can define different pedal faces and fences, to help position the sole of the foot for best effect.

The pedal faces are also down to driver choice – either being bare carbon fibre, with grip tape (typically for the brake pedal), or conversely slippery PTFE tape (occasionally for the throttle pedal). Then the braking effort is defined by the master cylinder sizes and the throttle pedal effort and sprung return, being tailored in the throttle damper assembly.

Finally, there is a heel rest for the driver to brace their foot against when modulating the pedals. This can be a simply flat plate or more commonly a double-U shape, with each foot resting in a “U” shaped carbon moulding under each pedal.

In between the dash bulkhead and pedals is an “M” shaped foam pad, to protect the driver legs hitting the inside of the footwell and steering column in the event of a crash. The basic shape of this pad is defined by the FIA regulations, but some drivers will have a bracing pad fitted below the steering column to stop their legs moving sideways in high ‘G’ corners. Some drivers also choose to wear knee pads over the race suit to stop their knees knocking together.

Lastly, the rear view mirrors can be refined, although their position is quite tightly defined by the regulations. Drivers will need a clear view behind them, not simply to react to a following car, but also there is a FIA test to check rearward visibility when seated in the cockpit. The driver may also want to alter the small clear ‘windscreen’ at the front of the cockpit, but this would be altered more from on track experience than at the seat fitting.

Moreover, the seat fit isn’t a one-time specification fixed in perpetuity. As drivers start to test and race the car, the seat fit definition will change. Mainly detail changes to padding, positions and steering wheel layout. But even different seat moulds may be taken to suit a driver mid-season. While Michael Schumacher had inflatable bladder ‘cushions’ fitted to his seat, so that they can be inflated to get exactly the right level of support for him during a session.

PROBLEMS FITTING IN

Most drivers find a perfectly good seating position from the first seat fit and make very few subsequent changes. But drivers of a non-standard size will have problems, it’s well known Nico Hulkenberg struggles to get his tall frame fitted into the car. If a team know that a taller driver will be their race driver, they can make adaptations as they plan and design the new car.

For George Russell, the sudden promotion to Mercedes race driver in Bahrain last year created some problems. As George previously had a seat fitting at Mercedes, his choice as stand-in race driver was convenient as a seat mould was already available. However, he hadn’t fitted for the current monocoque and his position was compromised as a result.

Russell is very tall for an F1 race driver, very much the antithesis of the typical jockey sized F1 drivers. As a result, he also has much larger feet, size 11 (UK), whereas size 6-8 is more common.

Firstly, this placed him much higher in the cockpit, still below the critical imaginary roll hoop line. As mentioned above, this puts the helmet well above the usual position behind the windscreen, placing it in more turbulence, plus creating yet more turbulence ahead of the roll hoop inlet and rear wing.

Then, within the footwell, the well-intentioned FIA minimum cockpit dimensions worked against Russell. The front (A-A) and dash (B-B) bulkheads have a minimum cross section, the taper of the footwell in between them must be linear. For aerodynamic reasons, teams would prefer to keep the cross sections are close to the minimum as possible. With a ‘standard sized’ driver, this isn’t a problem, as a size 8 foot being 26cm long fits into the available space.

When Russell’s feet are some 3cm longer, there becomes a problem. The available height within the cockpit footwell simply doesn’t allow for them, especially as his long legs push the pedals forwards into the narrowing footwell area. As a makeshift solution, the pedals were adapted, and Russell wore size 10 race boots to squeeze his feet into a smaller space. Not comfortable, but given the opportunity afforded to him, a price worth paying and not one that unduly hampered his excellent performance during a one-off drive that so nearly ended in triumph.

This does give rise to the question are the FIA cockpit sizes worth reviewing? That’s certainly a consideration, but with the 2022 regulations already published an opportunity has been missed and one foe the FIA Safety department to consider for future F1 rules and perhaps earlier adoption with Junior categories as the spec chassis comes up for review.