Since its inception, motorsport has seen driver wear specific clothing for racing. The challenges of driving and the dangers it poses have shaped the racewear worn from head-to-toe over the years. For most of its history the biggest danger was fire, exacerbated by chassis that crumpled in a crash, damaged fuel tanks leaking fuel and the danger a driver might be trapped in the burning wreckage.

Thus, fire protection has long been the number one priority for racewear. While recent events at Sakhir show fire is still a risk, lots of other factors come into play with the current race driver’s outfit.

Racewear is a compromise, it needs to be comfortable to allow the driver to be fully to have confidence whilst driving the car, while it also needs to provide protection in case of accidents. When Romain Grosjean emerged relatively unscathed from his blazing Haas wreckage in Bahrain, both the Halo and his protective Nomex race suit had everything to do with his survival.

When we talk about comfort, there’s several factors; the driver needs to be able to feel the steering and the pedals, they also should not be constrained by a heavy suit that doesn’t stretch as the driver’s body does. But also there the issue of heat stress, a driver getting too hot soon loses performance. Driving an F1 car for nearly two hours in high ambient temperatures, suffering 5g forces and exerting 130kg of brake pedal force is an athletic endeavour.

For safety, as outlined above fire is the greatest danger, then there’s the impact protection required of the helmet and the neck protection of the HANS device.

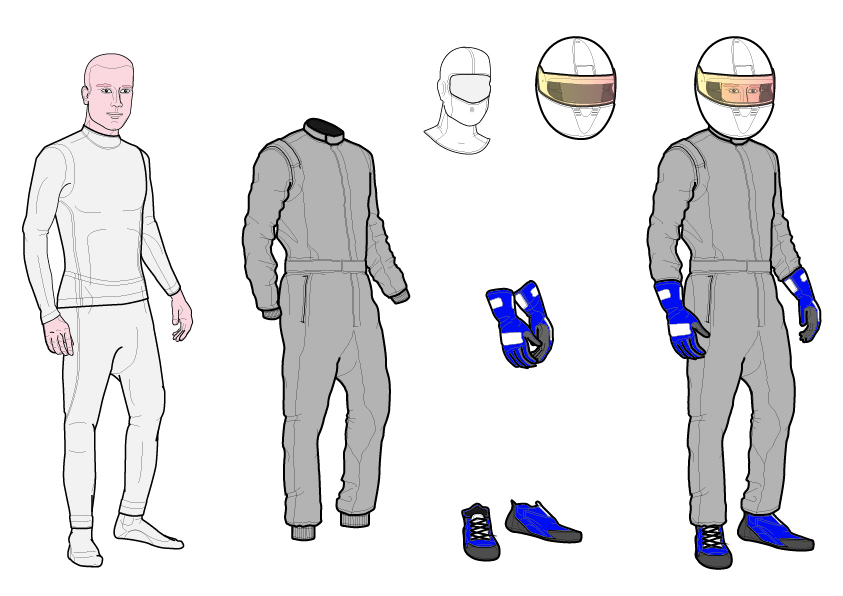

Current Driver racewear hasn’t changed in summary since the sixties, there’s the driver race suit, fireproof underwear, gloves, boot and helmet. But the current breed of race wear is far superior on both protection and comfort compared to every decade preceding it. Enforcing the safety of this outfit are FIA regulations, with 8860 covering helmets and 8856 the clothing.

Regularly the FIA safety department looks at the regulations, development in technology and the result of incidents, any of which might prompt updates. Currently both regulations were updated in 2018, adding that number as a suffix to each of the regulations. Most commonly these are applied to F1 first and trickle down through the other elite categories and junior level racing.

Race Suit

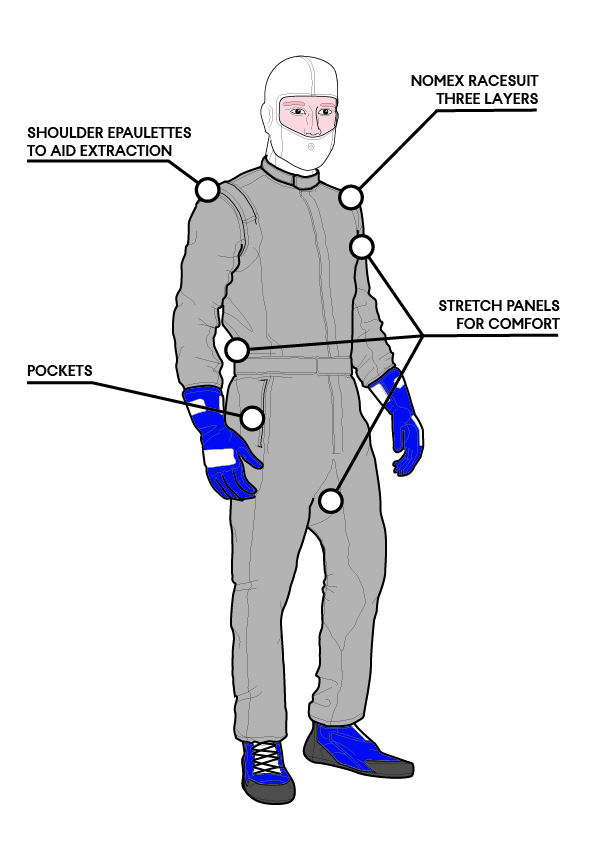

Fundamental to the rear wear is the one piece race suit now subject to regulation 8856-2018, although the revised suits are only mandatory F1 this year.

Taking the safety aspects first, the suit is made from Nomex material, a fireproof material developed by Dupont. This material superseded equally fireproof materials that existed before, but these tended to be cotton with fireproof treatments. While they had the fire protection when fresh and new, with wear, washing or contamination from fuel\oil etc they would lose their properties. Thus, the intrinsically fireproof Nomex has become the de facto material for fireproof race wear. Over the years the material has been developed, so has become thinner and lighter, which will help with the comfort factors which will be explained below.

Current race suits are made with three layers of fabric, to meet the fire resistance test as required by the FIA. The time used to be 10s at 800c under 8856-2000, but now its 12s to confirm to the current rules. This test is also now applied to the seams and stretch panels, to prove the whole suit provides the same level as protection as the main construction. Additionally, the suits must now feature an expiry date, so that the suit isn’t used beyond its safe service life.

Once proven to have passed the FIA tests, every suit must have the certification type and expiry date embroidered into the neck of the suit. Manufacturers once tried to print these details, but the F1 scrutineers quickly rebuked this practice. As a print could be worn or burn away, while the fireproof thread is more permanent and thus longer lived, especially in the event of an accident.

To keep the flames out, the suit has tight fitting wrists, ankles and collar, plus the zipper must have a flap covering its full length. Safety also goes as afar as the suit having epaulette loops at the shoulders, to assist marshals in pulling a driver from a car, as was the case with Grosjean’s escape.

Needless to say, each suit is tailor made to each driver, clearly a well-fitting suit adds to its safety performance.

Thus, it reflects the driver’s size and shape, but also as well as their preference for comfort. While most drivers now have a close fitting suit, someone like Jacques Villeneuve preferred a baggy suit. Most suits even have pockets, although who knows what an F1 driver needs to carry around with them nowadays! Certainly not his car keys.

With fire resistance covered in the suit’s materials, driver comfort is in the details of the suits tailoring. Firstly, suits tend to be cut with a front to rear bias, as the driver is a tucked position in the car. The back of the suit is longer, or features stretch panels, whilst the front is shorter to prevent is rucking up uncomfortably under the seat belts. Likewise, there are stretch panels where the sleeve meets the body and in the crotch area. These stretch panel help with comfort but underline the important of the increased testing with the new rules. Then all of the seams are sewn flat to prevent them cutting into the driver when tightly strapped into the seat.

Back in the seventies, the suits used up to five layers of nomex, with felt-like layers in between them order to provide the fire resistance. This made the suit like a winter blanket, making for less manoeuvrability and keeping the driver’s body heat inside the suit. Now the latest lighter materials allow for the driver to articulate their arms and legs more comfortably. But just as important, the layers are breathable, allowing the driver body heat and sweat to escape, keeping the driver cooler and less prone to heat-stress and dehydration.

What’s more, the suits are considerably lighter, feeling more like a track suit and weighting 750g, than the old suits at nearer 2kg. To meet the more stringent 8856-2018 tests the suits are little lighter and more insulating than before, but only by a small margin.

Further helping in comport and weight, is the suits are no longer embroidered or adorned with sewn on patches, most of the livery is printed on by inkjet! This allows the sponsor logos and complex livery with multiple colours, fades and even photographic style print to be applied to specially treated outer layer.

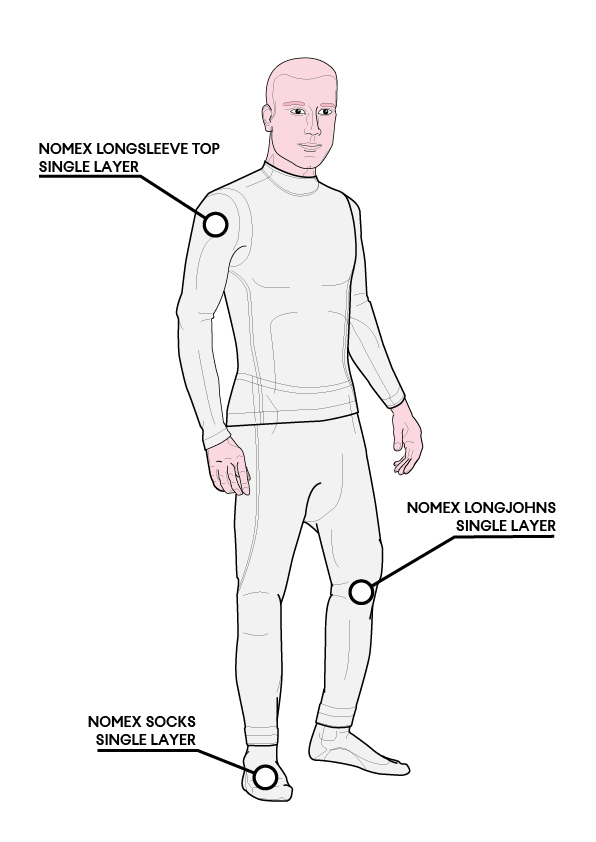

Underwear

Under the race suit, the drivers have to wear a layer of fireproof underwear. As with the suit this is subject to Reg 8856-2018 and the material is again Nomex. As with most sports the technology of this base layer has developed in recent decades, the old suits looking like woolly thermals, are now thin, breathable and moisture-wicking. So they meet the fire protection, but also provide the athletic comfort the drivers need.

There is along sleeved top, long john style bottoms and socks, its important these have a generous overlap in between each other to protect the driver from fire even in their seat position. Like the race suit, the underlayers need the regulation certification displayed and the material can be printed with sponsor logos.

Then there is the balaclava. This can have a double layer over the front to further protect the exposed facial area inside the front of the helmet. In the higher risk seventies and eighties, a double eye hole used to be preferred for slightly more protection. It seems nowadays the drivers all have a single larger eyehole, often pulling down over the nose or ever their mouth. To allow the tube for the drinks system into the driver’s mouth, these a hole stitches into the balaclava too.

British Grand Prix, Saturday 1st August 2020. Silverstone, England.

Inside the balaclava, often there will be the earpieces and microphone for the driver-pit radio, it varies by driver, as some prefer one or both to be inside the helmet. The benefit of having them inside the balaclava is that they are closer to ear and mouth. Plus, balaclavas are cheaper than helmets, so a number of spare balaclava/earpiece/mic sets can be ready if there’s a fault with the one the driver’s wearing.

Gloves

The gloves or gauntlets have always been a racing driver trait, from crochet backed or punched leather gloves of yesteryear, now drivers have some fire protection for their hands.

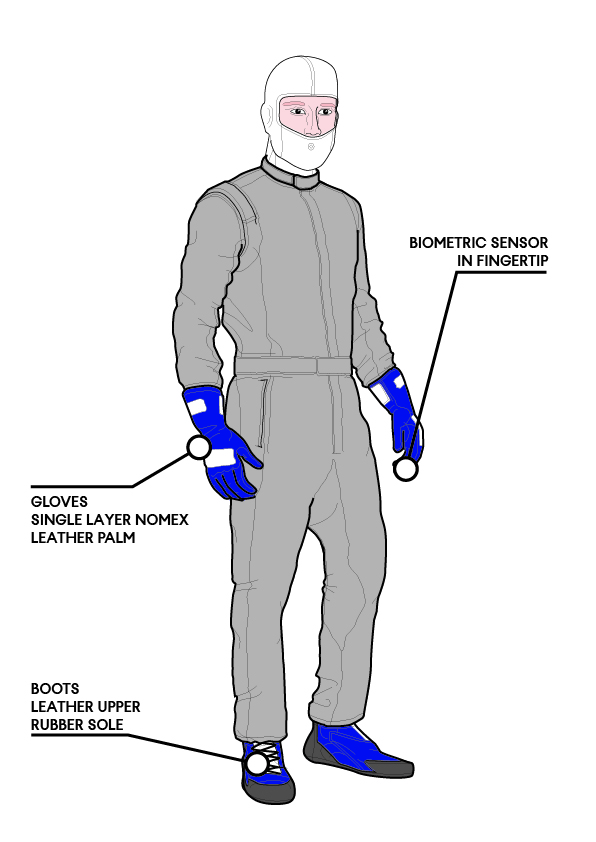

Fine leather palms provide the tactile feedback of the steering wheels silicone grips into the driver hands, then a nomex glove extends from the palm and fingertips. Again a good fit is essential for feedback and safety, with some manufacturers and drivers preferring Velcro straps at the wrist to keep the glove tight against the hand.

This construction is a compromise, more Nomex layers would be better for fire protection, but then there’s be less finesse for the driver’s fingertips. So, there is less fire protection accepted from the gloves compared to other parts of their race wear. This was again proven in Grosjean’s accident, where his hands were the most affected by the fire, as there were fewer layers of Nomex protectivity.

Never thought that a few body weight squats would make me happy. Body recovering well from the impact . Hopefully same about the burns on my hands. 🤞

Thank you again to everyone for the messages.

Ps: still very slow at typing 🤣#r8g pic.twitter.com/PHr5nMZsZG— Romain Grosjean (@RGrosjean) December 1, 2020

Unbeknown to most fans, the driver’s gloves also feature a recent safety innovation, a biometic sensor. Inside one of the fingertips is a wireless sensor, reading the drivers vital signs; heart rate and oxygen saturation. Data from this sensor is fed back to the cars Safety Data Recorder and can be access wireless from outside the car. This not only provides real time and logged data on the driver’s health status, but in the event of an accident, the marshals and medical team can establish how critical the drivers condition may be and make judgement called based on that.

Should an accident result in the medical team unable to reach the driver, knowing if their heart rate or breathing is critical – the medical team might decide to forego some recovery procedures to extract the driver more rapidly. For example if a driver was unconscious and trapped in an inverted car, they might turn the car over more quickly, perhaps risking a skeletal injury, in order to prioritise giving treatment for the driver’s breathing\heart rate.

Boots

Racing boots seem to change with the times and often reflects other fashions in footwear. As with gloves, boots are a compromise, erring on feedback over absolute safety. Current trends follow a sports trainer style, with Velcro straps or laces and a thin silicone rubber sole. Most recently, has been the trend for sock style uppers, rather than the leather\suede or manmade leather-like materials.

Helmet

Leather flying helmets were soon lost to fibreglass shelled helmets, initially open-face and then closed, with visors over goggles. Current F1 spec crash helmets are incredible feats of engineering and subject to some very stringent tests. The prevailing 8860-2018 regulations have already filtered down to other race categories and are an evolution of many themes in helmet over the past decades.

A helmet is formed from a carbon composite outer shell, a foam liner and fireproof lining, each aspect of these is tested to meet FIA approval. Most recently the regulations have sought to lighten the helmets while meeting the impact resistance test, a lighter helmet, whilst being more comfortable at 5g cornering and braking, is also safer in a major accident of up 50g, reducing neck injuries, the HANS device notwithstanding. Depending on the size of the shell, an F1 helmet will weight just 1250g!

Steiermark Grand Prix, Friday 10th July 2020. Spielberg, Austria.

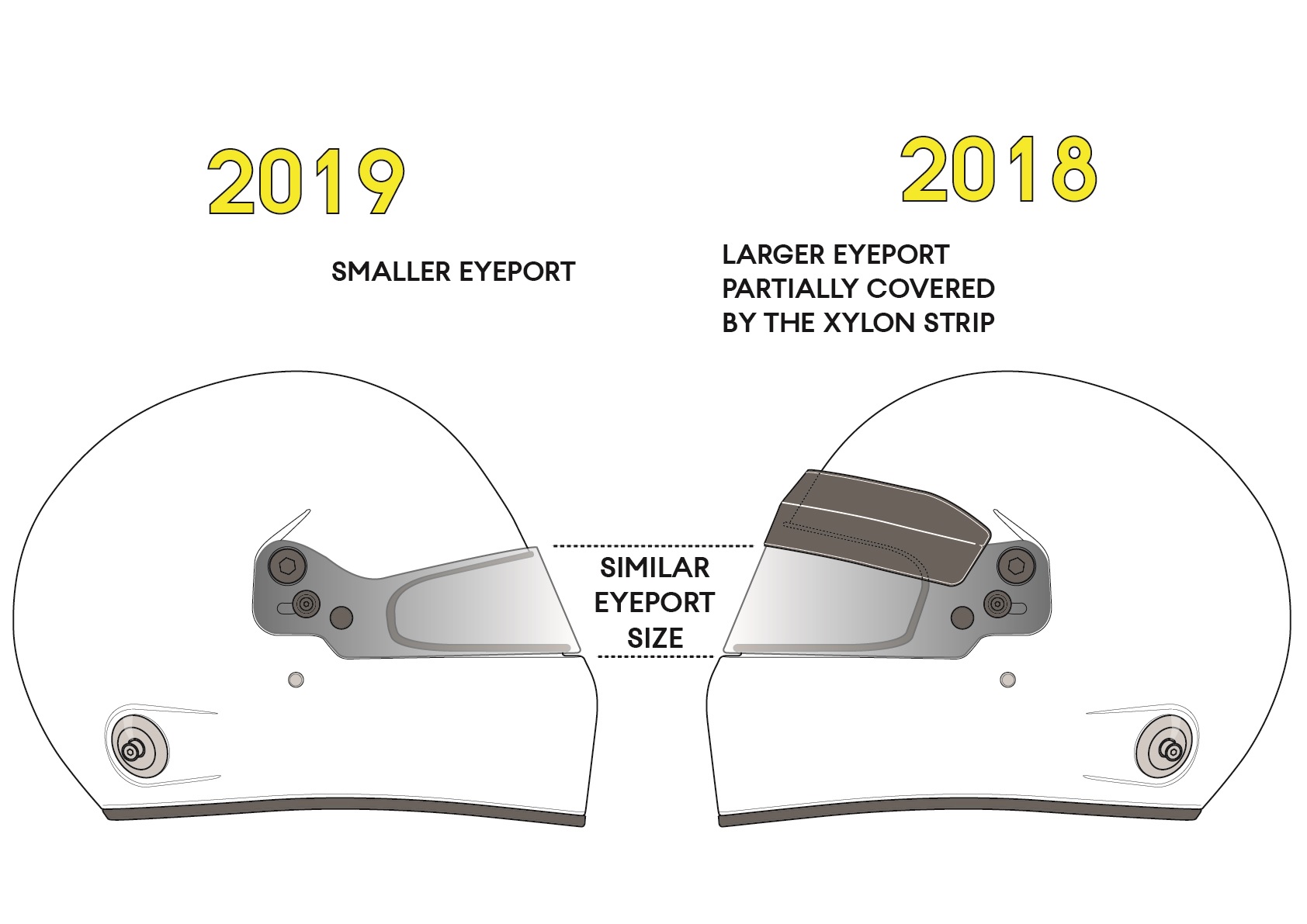

Key to the -2018 regulations was the change in the eye port size and visor overlap. After Felipe Massa’s accident where his helmet shell was breached by a metal coil spring hitting the helmet\visor at speed, the FIA enforced a Zylon strip to reinforce the overlap between visor and helmet. This was superseded by the new rules, where the visor opening is smaller and the area around the opening is reinforced, negating the need for the added strip. The apparent reduction in driver visibility is not an issue as the old visor sticker or zylon strip covered the same area, so the effective window area formed by the helmet\visor is the same.

Those recalling the seventies and eighties in F1 will recall the tube going into the driver’s helmet, linked to a special medicated gas supply to allows the driver to breath in case of being trapped in a fire. As safety standards with racewear, the car and trackside operations have improved these systems were no longer required and are no longer to fitted the car nor required by the regulations.