The Formula 1 pit stop has become an essential part of Grand Prix theatre.

Bringing a car into the pits, stopping it, replacing all four of its tyres and releasing it in less than two seconds, is not only a breathtaking human and technical achievement – it can decide the outcome of a race.

Time lost or gained in a stop is as essential as time lost or gained anywhere else in the performance envelope – be that via engine performance, aerodynamics or braking.

As recently as the Spanish GP, a ‘slow’ three-second stop for Mercedes driver Valtteri Bottas compromised his fight for second place with Ferrari’s Sebastian Vettel. Had Bottas’ stop been of the regular two-second duration, he would have exited the pit lane just ahead of his rival. As it was, he exited just behind, so had to set about passing Vettel on track. This example illustrates how the modern F1 pit stop is used to gain strategic advantage: their purpose is far more significant than simply changing tyres.

In this example, Mercedes and Bottas had tried to achieve what’s known as the ‘overcut’. Vettel, running second, pitted on lap 17 to emerge around 20 seconds behind Bottas. Now Bottas’ Mercedes could run in ‘clean air’ rather than in the turbulent wake being left by Vettel’s Ferrari. For two laps, Bottas was told by his race engineer to drive as hard as he could before pitting himself. As the Mercedes was the quicker car, Bottas was able to drive 0.6s a lap faster than he had been behind Vettel – gaining him an overall advantage of 1.2s over Seb. This should have been enough to let him pit and return to the track in second place. Unfortunately for Bottas, a small delay changing his right-rear tyre wiped out the advantage he’d gained and he remained in P3. This was a rare fumble from Mercedes, who hold the current pit stop record for a 1.83s turnaround achieved at this year’s Chinese GP.

An alternative version of this scenario is the undercut, whereby a faster driver running behind a car that’s slightly slower, but not slow enough to allow an on-track pass, will pit first, change tyres, then return to the track in clean air. The driver will then sprint for two or three laps, waiting for their rival to pit, hoping that they’ve gained enough time to emerge ahead when both drivers have completed their stops.

F1 pit stops explained

So much for the strategic considerations: what of the stops themselves?

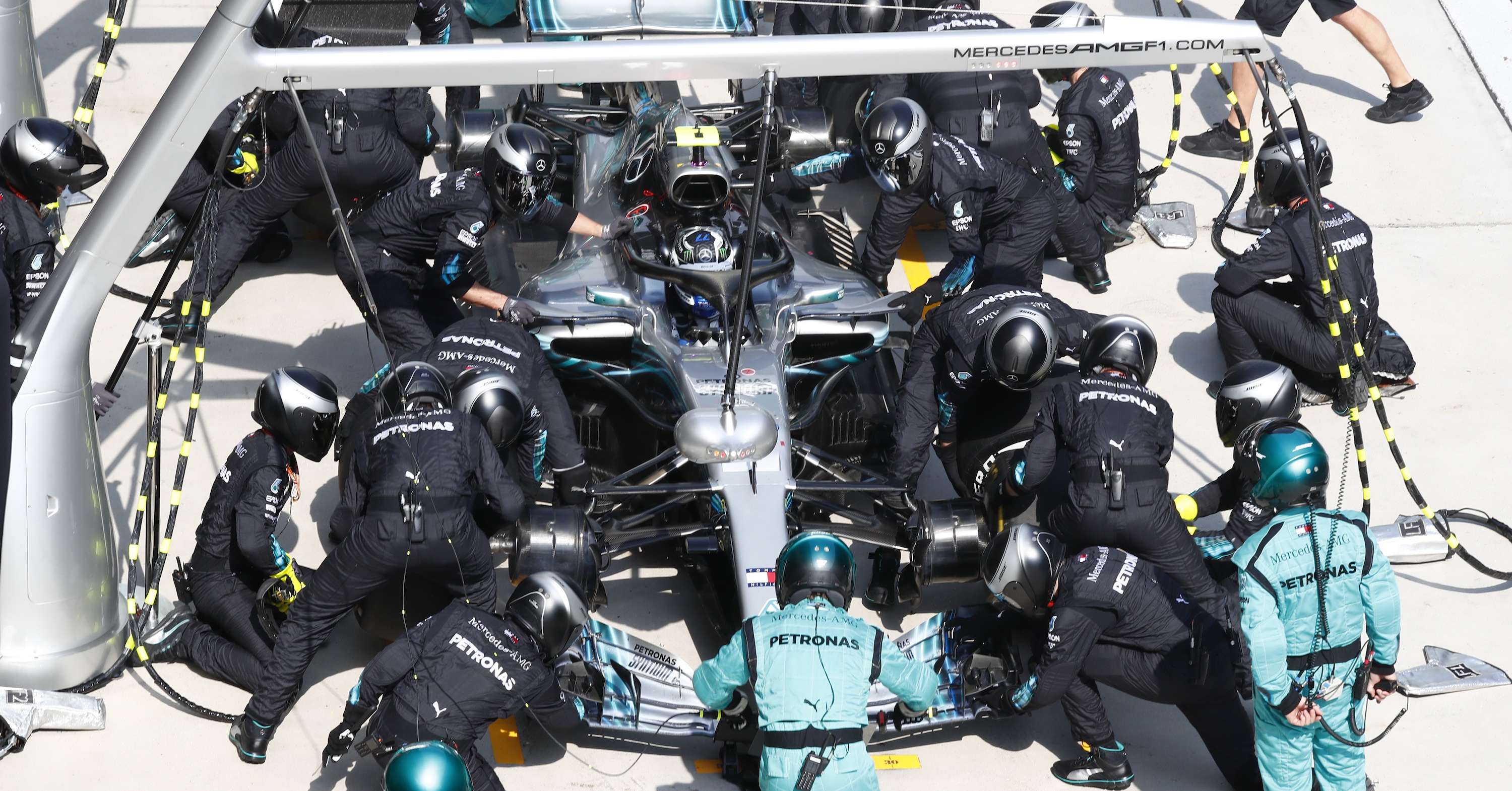

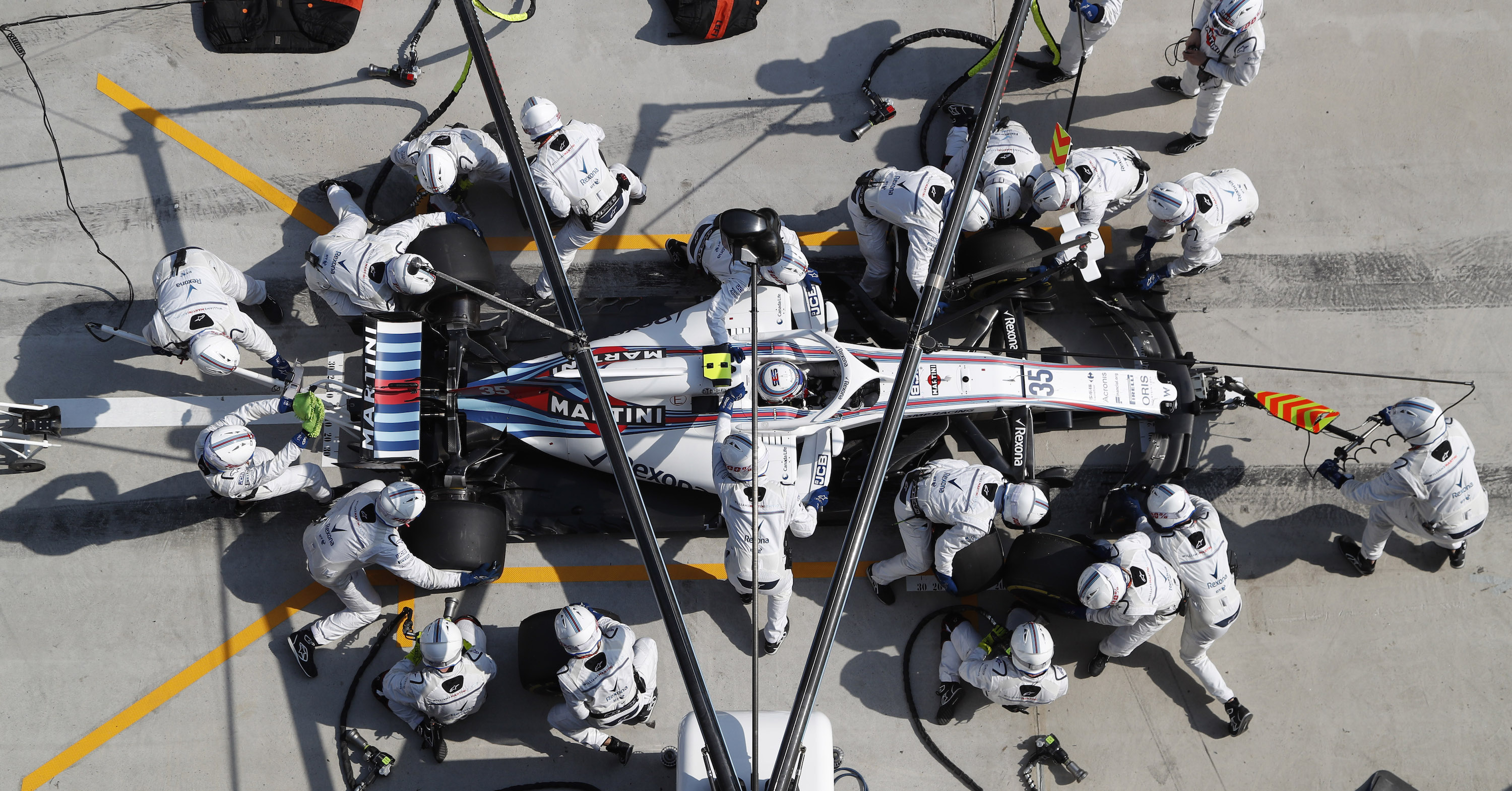

As can be seen during any grand prix, pit stops have become intricately choreographed maneuvers, involving up to 20 people.

The balletic performance relies on each member of the pit crew – all of them mechanics – performing duties that they drill and re-drill so that they can be performed flawlessly even under the extreme pressure of racing. Typically there’s a three-man team on each corner of the car. When a car stops ‘on its marks’ – lines painted onto the pit box where a driver must stop precisely, so that his pit crew don’t have to change position – swivel jacks (each of which cost €80,000) are thrust beneath the front and rear of the car to raise it a few inches from the ground. All the while, the driver must keep his foot on the brake pedal, to prevent the wheels turning during the change.

Then the wheel-gun man first places a high-pressure airgun over the wheel nut to ‘spin’ it off. As the nut is released, freeing the wheel, a second mechanic already has his hands on the used wheel/tyre to pull it from the hub. Almost simultaneously a third mechanic places the fresh wheel/tyre on the hub and the wheel-gun man returns to tighten the nut. The car is dropped and released – but not before what’s known as the Automatic Release System (ARS) has been activated. This is designed to ensure that the car isn’t set free from the pits until all four wheels have been safely changed.

ARS relies on sensors which monitor jacks and wheel guns and which can trigger the pit stop lights which tell a driver when it’s safe to go. There’s also a regulatory requirement that each ‘gun’ man has to push a button to signal ‘OK’.

When the ‘OK’ is received from both fronts and both rears, the jacks are dropped and the driver gets a green light.

But despite all the training and sophistication, things still go wrong. At the Bahrain Grand Prix, Ferrari mechanic Francesco Cigarini was driven over by Kimi Räikkönen as he exited the pits. Ferrari’s ARS system had become confused by a repeated ‘release’ signal on the stuck left-rear wheel, which it interpreted as a wheel having been safely removed and replaced. As it was, the original wheel was left in place but unsecured and Kimi accelerated away while a Cigarini was still working on his car. The unfortunate mechanic suffered a double leg fracture and Räikkönen was forced to retire from third place. Ferrari were also fined €50,000 for an ‘unsafe release’.

As in so many areas of F1, the quest for speed and technical perfection often leave teams teetering on the edge of fallibility.