A major rewrite of the F1 technical regulations has been in the pipeline for years. Finally, after being delayed by a year, the FIA unveiled a show car demonstrating the very different look of the 2022 F1 car.

What we saw isn’t an actual F1 car, merely the sport’s interpretation of the new rules. However, this is enough to get a feel for this new era, with bigger wheels and low profile tyres, aerodynamics aimed at improving overtaking and a dramatic new ‘look’.

We can see the new concept has larger underfloor tunnels, aimed at creating more downforce from beneath the car, a sloped nose/chassis leading back to swept sidepod inlets. The front wing gains triangular endplates and the rear wing is reduced to an endplate-less upper design.

New details are the front tyre fins and a return to wheel fairings. In this set up the car has been proven to reduce the turbulence it leaves in its wake, while the underfloor and wings lose less downforce and balance in another cars wake.

F1’s technical regulatory framework has evolved over many years, with the rulebook going from a few pages to over a 130-page document in 2021. Whilst the process to establish new rules has changed very little until the past few seasons, historically the rules have been created without engineering rigour, the change coming about from a political desire to alter some aspect of the sport, typically slowing the cars or improving safety.

Often kneejerk in their response to recent incidents, the resulting regulations were rarely thought through, evaluated by peers or achieved their goals. Teams would find loopholes, different interpretations or workarounds to circumvent the intention of the rules. This has increasingly led to a rule set that is overly specific and detrimental to either overtaking or costs.

Only the work with the Overtaking Working Group for the 2009 rules avoided the mistakes of the past. As the teams invested their own money into a limited aero research programme on the problems of overtaking. But this was a one off project and never developed beyond the 2009 ruleset. With the acquisition by Liberty, came a change in F1’s governance, as Ross Brawn took on the role to look at future rules and the problems perceived with the current F1 car and rules.

This technical group is like an eleventh team, with enough engineers and resources to fully analyse the objectives of improving overtaking, with due diligence, not changes based on hunches – Pat Symonds, Jason Somerville and Craig Wilson heading the research group. This change allows the group to research the problems and then not only suggest changes, but test those changes too.

Not simply blindly following the intent of the change, but taking a ‘poacher turned game keeper approach’, i.e. what would they have done back in their F1 teams to circumvent the rules? As a result, the new regulations have been tested and reconsidered many times before being published. While no doubt there will be different interpretations of the rules, this is a far more effective regulatory approach than has ever been used before.

As mentioned above, the key aim of the rules has been to allow the cars to follow each other much closer, allowing the potential for more overtaking without the artifices of high degradation tyres or DRS. The two underlying issues are the aerodynamic wake the leading car creates and how sensitive the following car’s downforce producing surfaces are to that turbulence.

If you can control both whilst still maintaining the current cars performance, then the on track action should improve. There are other factors within the new rules, such as cost control and safety improvements, but this article will seek to focus largely on the aerodynamic changes shown on the 2022 concept car.

Setting things straight

Ahead of the British GP several show cars and renderings were presented, which may confuse many fans. So firstly, lets clear up some of the confusion raised from the various unveilings.

Straight off the car shown on the grid with the drivers is a show car, merely the FIA’s interpretation of how the new cars may look. By the time we get to pre-season in 2022 each of the teams will have developed their own car, this isn’t some form of spec formula creeping into F1.

Thus, given the teams resources and desire to find performance differentiators to the early FIA concepts, their cars will look different in detail, whilst still having to fit within the tight constraints will follow the general form of the cars seen so far.

What will be missing are the complex aerodynamic add-ons like bargeboards, fins and flaps. These new rules are worded to keep bodywork shapes more fluid and uncomplicated.

On the subject of spec parts, there was a move from the sport when planning these rules that there would be a long list of standard mechanical parts that teams all had to use. This plan has been diluted, so while there are a few notable spec parts added under the skin for 2022, the bulk of the car is still the team’s own design work.

Initial criticism of the show car focused on the large nose and boxy sidepods. These are areas with a degree of freedom for the teams to design own their shapes, so we will still see slim noses and tiny sidepods. As the show cars were not fully resolved working race cars, several parts were not evident on the cars, things such as the DRS pod and the front wing adjusters, these are all still legal and will be visible on the cars next year.

Therefore, DRS will still be around for 2022. It’s intended the rules should negate the need for DRS to allow cars to make an overtaking attempt on a slower car, but DRS has been retained on what will hopefully be a temporary basis.

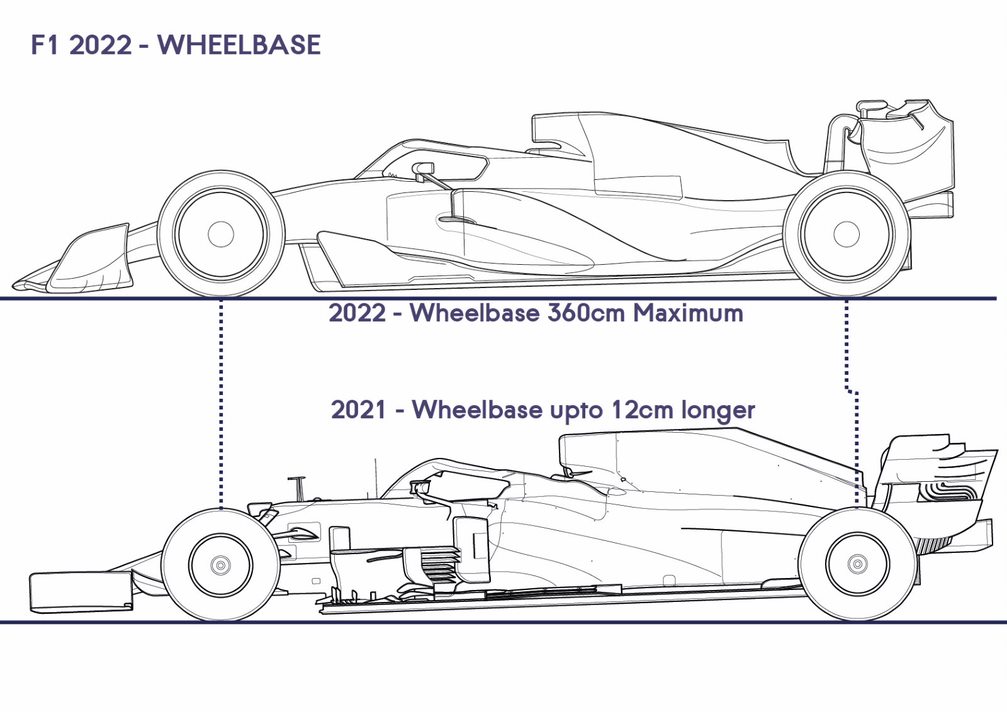

Fan criticism of the current 2021 car is the incredibly long wheelbase and excessive weight and there’s good and bad news on this front. The new rules finally enforce a maximum wheelbase, although at 3.6m this is still long by most race car standards.

Looking at the 2021 and 2022 cars side by side, the dimensions will be similar with the same width, weight and wheelbase. However, the teams at the extreme long wheelbase end of the current grid will be shorter by some +10cm. On the flipside, the car’s weight will grow to 790kg including the driver, largely from heavier wheels and tyres.

Under the skin

Changes away from the aerodynamics are long and detailed, but in summary the new cars will make the switch to 18” tyres with low profile Pirelli tyres. Inside the wheels there will be bigger brake discs, although this is likely to only affect brake cooling and not braking distances.

Suspension design in terms of the complex inboard spring\Damper\Inerter set ups will become much simpler. Safety will be improved with anti-intrusion panels to the front bulkhead and side impact areas. Engine and fuel tank safety in major impacts will be tested, in response to the Grosjean accident, while flying debris will be contained with the rear wing and rear crash structure being tethered to the car in a similar manner to the wheels. There’s even a new tail-light for teams to use!

In terms of the power Units, they’ll be made to very similar regulations as currently, with homologation starting from the start of the season through to the end of the 2025 season. Likewise, gearboxes will be homologated for the same period, with the allowance for one upgrade. This excludes the carbon outer carrier, which the gearbox cassette sits inside, which can be changed to allow for different suspension geometries etc.

All new aero

Setting out the new bodywork rules, the wording has switched from linear dimensions from datums, to a CAD based cartesian co-ordinate system. This defines the surfaces and volumes in which the bodywork can or cannot sit, which translates much easier for the team’s designers on their CAD system.

Every area of bodywork has now been defined with these volumes and various geometric constraints, such as minimum radius on concave\convex surfaces and enforced tangential curvature.

This may seem confusing to the average fan, but similar restrictions were applied to the sidepods in 2009, taking us from complex shapes in 2008 to smoother lines in 2009, so this approach is proven to have worked.

The car is broken up into four major areas, firstly the floor with its longer underbody tunnels, then the front end, which is linked to the front axle line, the rear end linked to the rear axle line and the central chassis\sidepods linked to the cockpit opening.

In a similar way to currently, the teams can shift these areas around to find the ideal package for the car but given the wheelbase will be capped at 3.6m, their freedom is limited.

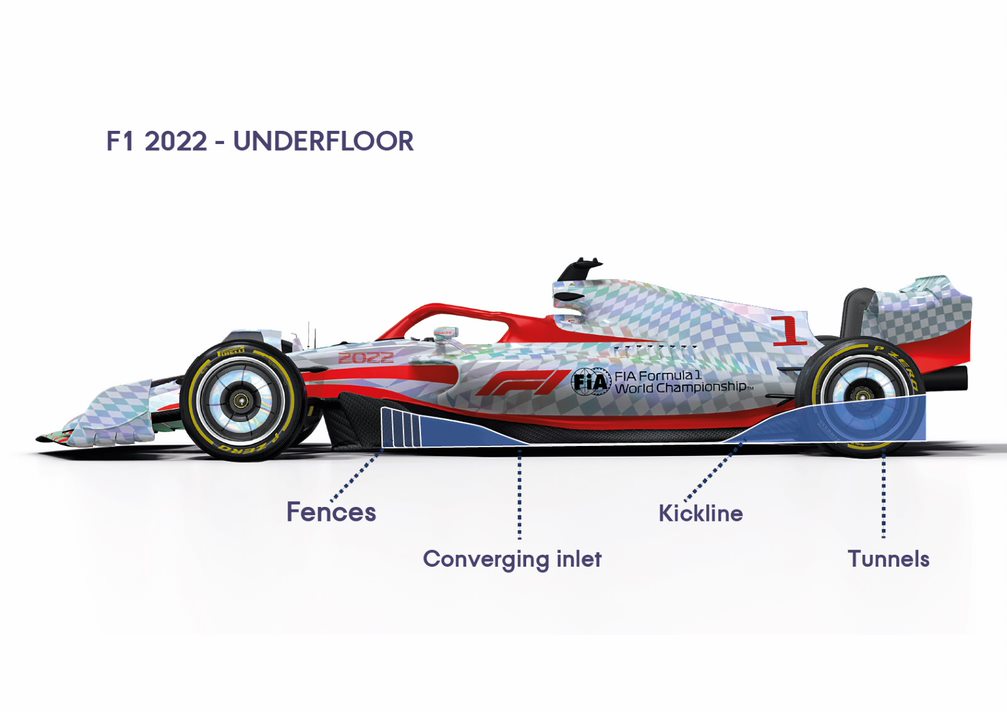

Key to the new cars aerodynamics is the underfloor, many people are calling this a ground effect car, which is at least partly right and at the same time partly wrong! Confusion comes from the times when the cars had huge underfloor tunnels, pioneered by Lotus and exploited with side skirts to produce huge amounts of downforce until banned in 1982.

The tunnels worked much better than wings as they were in close proximity to the track, exploiting an aerodynamic phenomenon known as ground effect. Although the skirts and tunnels were banned, the effect of a surface close to the track still benefitted from ground effect, so the current front wing and floors still work to an extent in ground effect.

The new underwing doesn’t use skirts, but does have a converging inlet ahead of the sidepods and leading back to a kick line where the larger diffuser starts well ahead of the rear wheels. This should create the larger proportion of the car’s downforce and the kick line being ahead of the rear wheels should afford the car a good balance too.

It’s thought the underfloor is less sensitive to turbulence compared to front and rear wings, allowing for the closer racing promised by these rules. Additionally, the effect of the large rear wing should help push the underfloor’s wake up over the following car, further aiding the ability to closely follow another car

Inside the mouth of the new floor, the team can fit up to four internal fences to manage the airflow under and out the side of the floor. There is also what’s called the floor edge wing. This is the bargeboard-like extension to the side of the underwing’s mouth that will keep the front tyre wake from entering the tunnels and push it outboard instead.

These devices and the support to reinforce them are likely to be a ripe development area for getting the underwing to work most effectively.

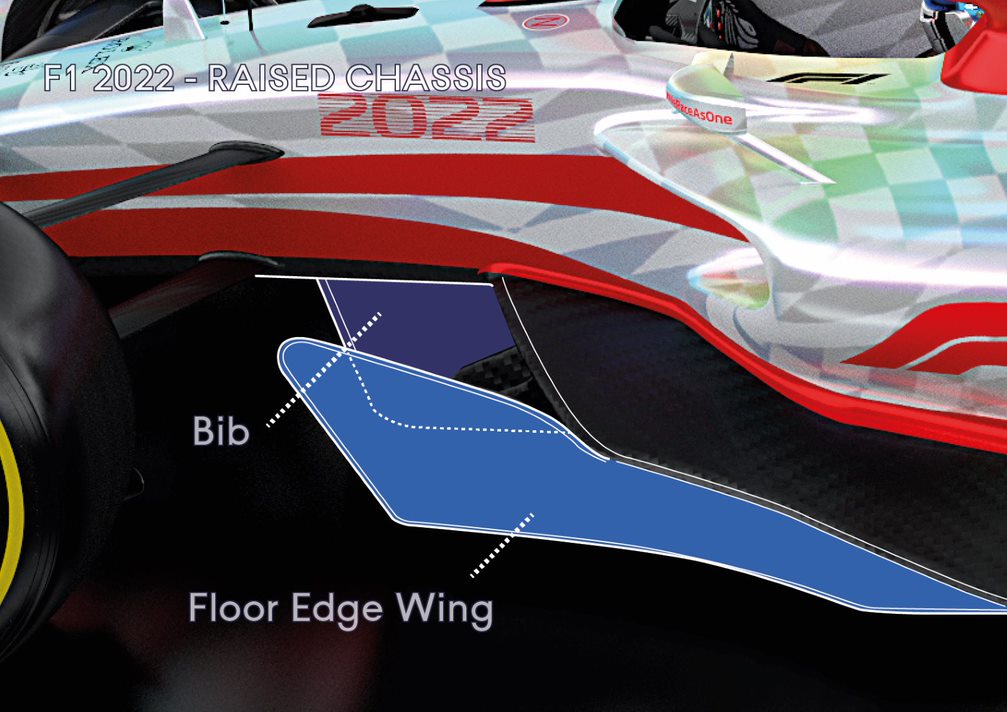

Under the raised chassis, the old T-tray splitter has gone and instead a heel like section is mandated called the bib. This will support the leading edge of the plank, which is retained in the new rules.

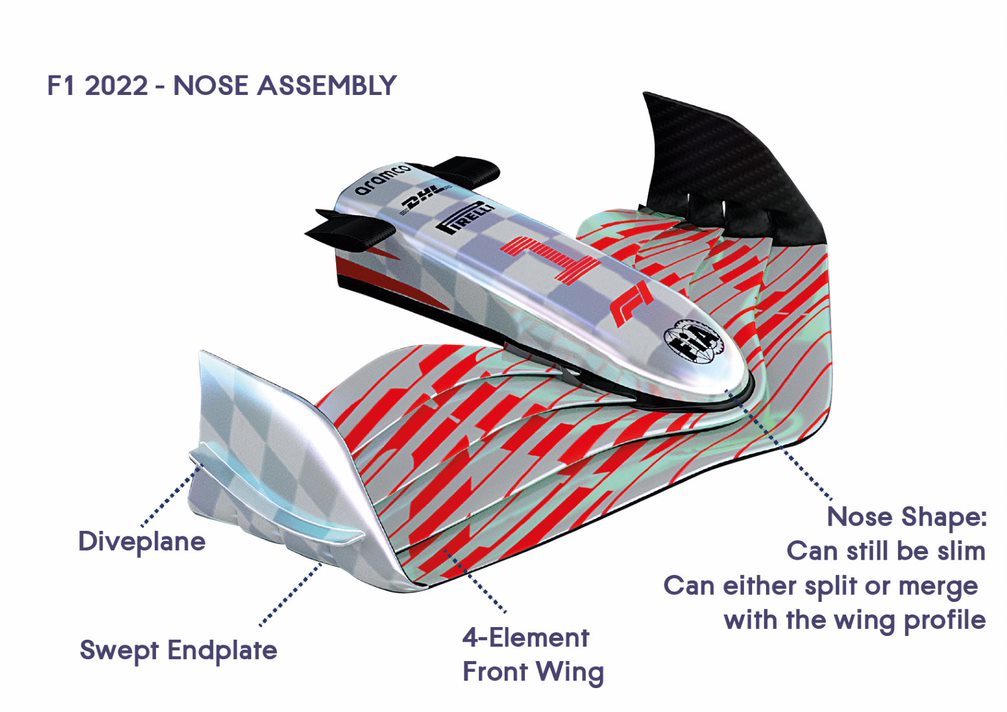

Already simplified since 2018, the front wing remains a clean design, limited to four elements within the regulatory volume it needs to sit within. The wing is also mounted higher, to allow for more airflow into the underbody and to make the wing less sensitive but now the profiles extend inboard to merge with the nose.

Thus, there is no longer the neutral centre span of wing, no Y250 vortex and no wing mounting pylons. Outboard, the wing profiles must merge and curl upwards to form the triangular endplate. This shape being an aesthetic addition, as with the rear wing endplate design.

There’s a small allowance for what’s called the dive-plane on the outer face of the endplate, which is used as a small flow control device setting up the air flow around the front wheel. How teams shape the wing profile is likely to be as varied as it is now, with inboard or outboard loading, to play between outwash and underbody flow.

As explained above, the nose, isn’t enforced to be a wide fat design. Teams do have similar tip cross sections to meet as now, but there isn’t anything precluding slim designs, if they pass the crash tests. With the added restriction on radii and tangential curves, the nose may not be able to feature capes as they appear now. There is some scope to play with the shapes, but the cape as a device might not be beneficial with the new underfloor shapes.

What may well visually differentiate the teams in the early years of these rules is the nose and wing intersection. The two volumes merge and what is defined as wing or nose becomes blurred and different solutions could be tried. Either a protruding nose tip with the wing profiles joining at the sides, or the nose merging into the front wing profiles.

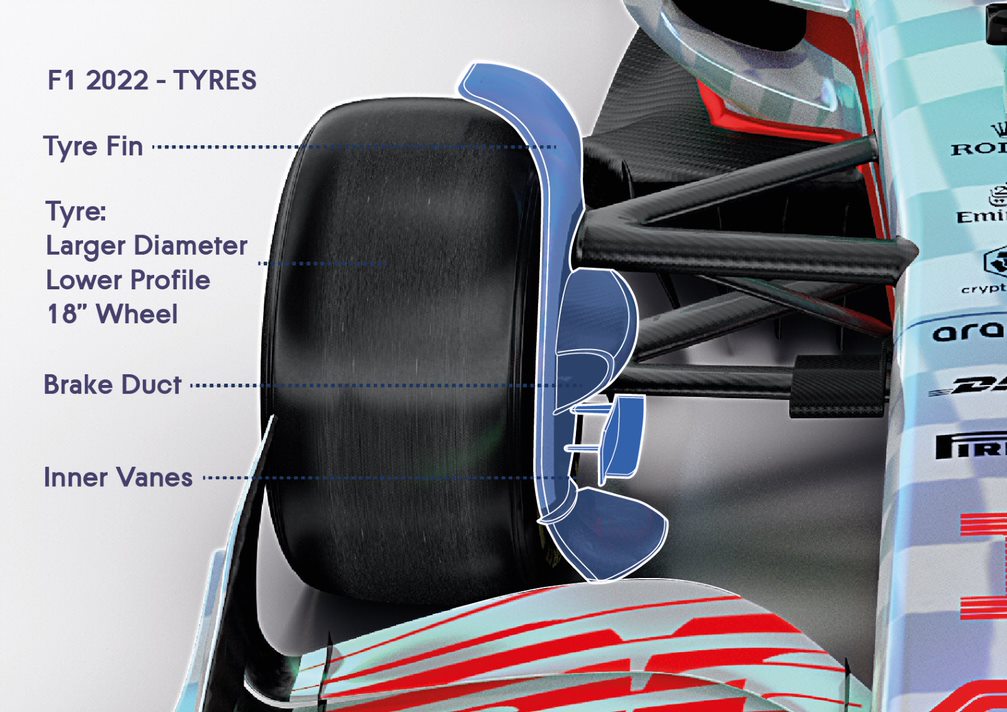

New 18” tyres and their wheels pose a challenge to the suspension designers, but for the aerodynamicists the good thing is the tyre should deform less than the large aspect ratio ‘balloon’ tyres used to date. We see a return to wheel fairings, this time fixed to the wheel, rather than the static designs last seen in 2009.

These wheel fairings greatly help to reduce the turbulence shed from the exposed spinning front tyres. Inside the brake duct area is changed, there being two add-ons new for 2022, the tyre fin and the inner vane.

The tyre fins are the small pieces of bodywork over the top of the front tyre. These aim to reduce the airflow separation that occurs behind the tyre, creating drag and turbulence. While the inner vane helps clean up the wake spilling off the inside lower edge of the tyre (tyre squirt) that might otherwise go into the underfloor.

It’s these devices around the front wheels that will greatly reduce the troublesome wake that trails behind the car and affect the following car so much.

Although not yet introduced, the rules do reserve the right to add display panels to the wheel fairings. This would allow quite high definition colour images to be displayed from LEDs on the spinning wheel fairing to be seen trackside on TV. The technology has raced in other categories before and exists in prototype form for F1. But its introduction is as yet unclear.

While not necessarily aerodynamic, the bodywork volumes also affect the front of the monocoque, between the cockpit and nose. This is currently flat and finally slopes down to meet the nose. The upper surface will be sloped for 2022 along its entire length, making for a sleeker look. It’s been pointed by fans that this might entice another car to rise up the nose towards the cockpit in a collision. With the nose height being similar to now and the added protection of the halo, this problem may be more perceived than real.

As with the nose/front wing, the sidepods are likely to be another area of differentiation between the concept car and the team in 2022. The reference volumes create plenty of space for the sidepods by creating a wedge shape inlet, mid sidepod and coke bottle volume for the teams to work within. There is also a new allowance for a large cooling aperture further down the sidepod.

How teams tackle this will be fascinating, the elongated inlet seen on the show car will not necessarily be directly copied while the high inlet and large undercut shape could be retained from the current cars. Given the potential size of the cooling aperture, some teams may choose to lose much of the coke bottle exit and instead use the aperture to its maximum!

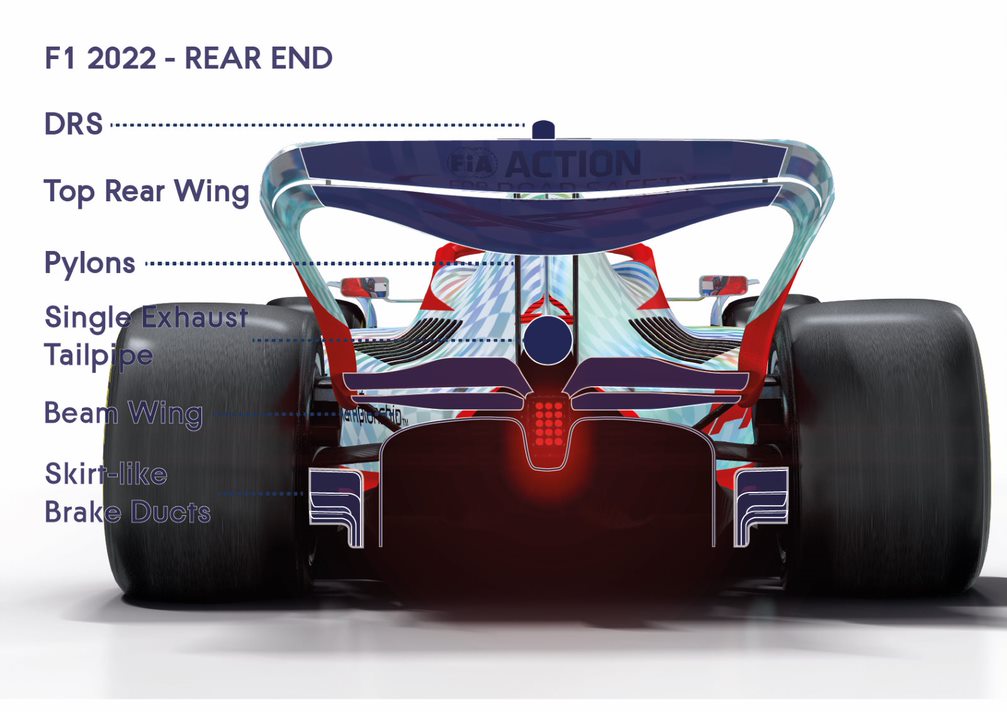

Forming the rear end package, the top rear wing remains a high and wide two element set up, now bolstered by the return of the beam wing, also in two element form. The top rear wing is somewhat handicapped by the endplate-less shape enforced by the rules. Although this again reduces the wake created by the wing. While the beam wing should help with expanding the airflow out of the underfloor tunnels.

Splitting the beam wing will be a return of the single exhaust tail pipe. This was split into 2-3 pipes to increase the loudness of the cars after the Hybrid power units were felt to be too quiet in 2014. Now the wastegate pipes must merge with the tail pipe, which itself is restricted in size, position and angle to prevent any overt blown effects being exploited.

Atop the wing there remains space for a DRS pod and up to two wing support pylons. Given the beam wing can act as a rear wing support, there may be a decision for the team to opt between a structural beam wing or wing pylons, balancing aerodynamics with weight.

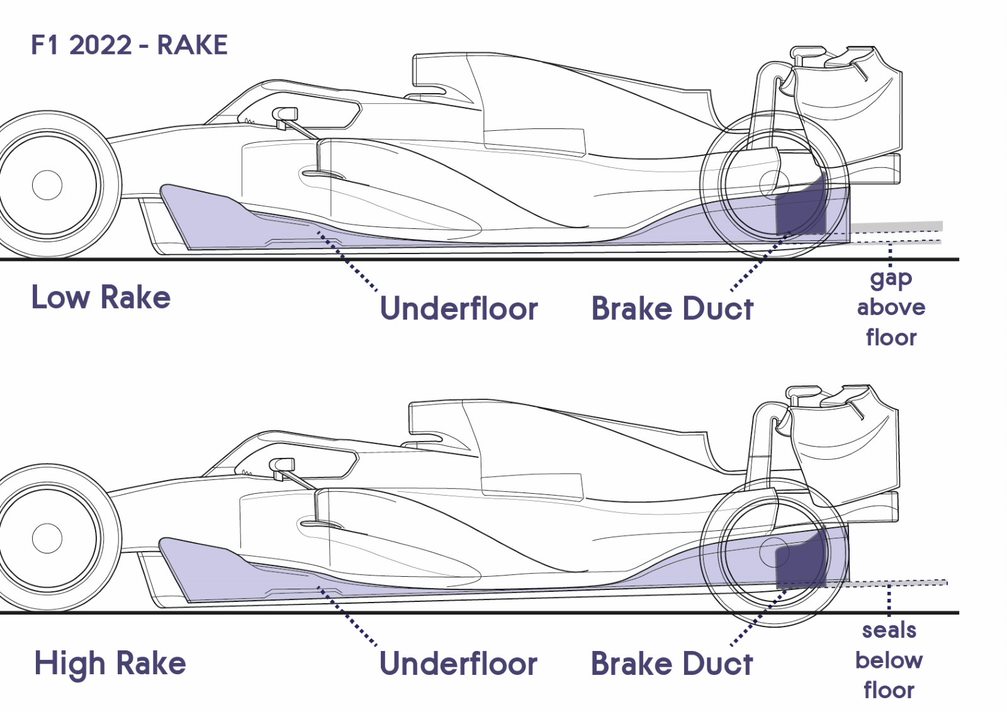

Finishing off the rear end are new quite extreme rear brake ducts. These lack the tyre fin of the front brake ducts but are allowed to have a deep skirted vane reaching down between the diffuser and tyre. These are also likely to be rich areas for development and fundamental factor in deciding the cars layout/set up. The vanes will help seal the diffuser to create more downforce dependant on the car’s ride height will vary how they might work.

At low ride heights (low rake) they will barely extend below the diffuser, but at higher ride heights (high rake) they will easily sit below the diffuser and help form a taller diffuser set up. How much teams will opt for high or low rake will depend on how effectively they can get the underwing to work at that angle.

The reference volume for the tunnels is restrictive. It might be that at this early stage in development they cannot get the floor to work at high rake, meaning the gain from the brake duct vane is lost. This may well be one of the defining performance areas of the first season with these new cars.

The Scarbs Summary

With so much changing with these new rules, tyres, suspension, engine, gearbox and aerodynamics, the winners and losers are going to be hard to predict. Any team with greater resources is more likely to be able to investigate some areas more thoroughly, although the aero testing limits and budget cap go some way to equalise that advantage.

With big rule changes always comes the opportunity one team might get their car just right with some inbuilt advantage, such as the double diffuser with Brawn in 2009. So, a midfield team could make some gains early in this era but as 2009 taught us, the big teams soon copy and catch up. Conversely, there is the risk of a big team getting it spectacularly wrong, which is often the case with these sorts of regulatory upheavals.

Will these new rules improve overtaking? That’s the $140 million dollar question, the science and engineering work has been done, the changes should help, but there is mitigating factor with major rule changes, field spread. With stable regulations the teams tend to bunch up, converging on similar solutions and therefore performance.

With major rule changes there are the winners and losers and as a result performance varies wildly between the front and the rear of the grid. It may mean teams aren’t close enough on lap times to benefit from the effect of easier overtaking. It may take a while to fully evaluate but it does look like F1 is going in a good direction with these rules.