As Sebastian Vettel’s SF90 rolled to halt at the Russian GP a with a hybrid system failure, unimpressed that his fuel efficient 1000hp power unit had failed in a race for the first time in over a year, his radio message was surprisingly frank – “bring back f***ing V12s”. Unsurprisingly, however, it is a popular demand from drivers and fans of modern F1, but is this really a good idea or is the memory of F1 V12’s shrouded in romance rather than realism?

F1’s engine formula has changed multiple times over its long history. The V12 found its place in F1 as part of the post 1966 3.0 litre engine regulations, it was then somewhat disrupted by the turbo engines of the eighties, only to see a brief return as a 3.5l engine after the turbo-era, as the decade ticked over into the 90s.

During this time Ferrari, Alfa, Matra, Lamborghini, Motori Moderni (Subaru) and latterly Honda raced V12s, resulting in three drivers’ championships and five constructors’ championships over 26 years. In 1995, 3.0l engines were mandated and the V12 was subsequently dropped from 1996, ending fans three decade love affair with the V12.

WATCH: Onboard as Vettel tests new Ferrari V12 at Suzuka!

(Note: Really it's Jean Alesi in the last V12 Ferrari back in 1995 but still enjoy!)#F1 #JapaneseGP pic.twitter.com/T4iGIsJQyZ

— InsideRacing.com (@INSIDERACINGcom) October 1, 2019

Myth of the V12

During these three 3.0l decades, the engine configuration norm was the V8, most commonly the Cosworth DFV and its later derivatives. In that time there was also the 1.5l turbo engines with a mix of straight-4, V6 and even a V8 (Alfa Romeo). There was only one other format tried with a normally-aspirated engine with a W12 layout, run briefly by the Life team.

Through this time the V12 gained fans from two key features; the extra power, typically the V12s were more powerful than the off the shelf Cosworth V8s varying from 30-50hp advantage over the majority of the field, but it was the sound that won people’s hearts. The extra cylinders and higher red line meant that the V12’s exhaust note roared out of corners and wailed at full throttle along the straights. In a time when all motor racing was with the internal combustion engine, sound meant everything to fans. This was particularly apparent in F1, with the rather flat note to the Cosworth and the somewhat muffled turbos, meaning that the V12 shouted louder than its most of its rivals.

Ferrari consistently ran normally-aspirated V12’s through this period, with just the V6 turbos interrupting this between 1981 and 1988. Initially this was a flat-12 engine, which is effectively a 180-degree V12, although termed a boxer engine back in the day, this is in fact incorrect as the crankshafts were laid out with shared crank pins for opposing cylinders.

Ferrari opted for the 12 for two reasons; heritage and technical. Ferrari had always been about the engine, having historically raced V12s and fitted V12s to their road cars, the race-to-road cliché is applied heavily at Ferrari, so the V12 format would be an obvious marketing ploy for Ferrari. On the technical side, the choice was made for the greater power output, the lighter reciprocating parts and greater valve area provided Ferrari.

Choosing the flat-12 format was initially for the lower centre of gravity height afforded by the having cylinder banks laying horizontally at 180-degrees to each other, thus being far lower than the 90-degree V of the Cosworth. This aided the handling at a time before aerodynamics became the primary concern. As aerodynamics started to be applied as a science, with streamlined shapes and fledgling wings, the flat format continued to be a bonus. Wide but low, the flat-12 engine format lowered its profile ahead of the rear wing, Ferrari also realised the wide flat deck formed by the engine cover also provided a small degree of downforce. With the design talent of Mauro Forghieri and Niki Lauda driving Ferrari took three constructors’ championships and Lauda taking two drivers titles with this engine.

By the mid-70s Alfa Romeo returned to F1, looking at similar power and installation benefits with a similar flat-12 engine. This was installed in the Brabhams following their resurgence under Bernie Ecclestone’s management and with the Gordon Murray designed cars.

As the seventies neared their end, the aero philosophy made a step change with the Lotus introduction of Ground Effect, and the wing car was born with its shaped underbody. Ferrari’s power advantage still held fast, and despite inferior chassis and aero compared to the British ‘Garagistes’, so took another title in 1979 with the flat-12 equipped 312T4 wing car.

With the wing cars came greater compromises for the engine layout, the flat design blocked the long underbody tunnels, so Alfa Romeo switched to a true V12 layout with a 60-degree bank angle. This was raced by both the Brabham team in 1979 and the factory Alfa Romeo team, latterly Osella ran Alfa V12s in the post-wing car era. Also, re-joining the V12 fray was Matra with a new engine, similar to the Alfa in having a relatively narrow 60-degree bank angle during 1981 and 1982. These engines had over 500 horsepower and revved to a screaming 13,000rpm.

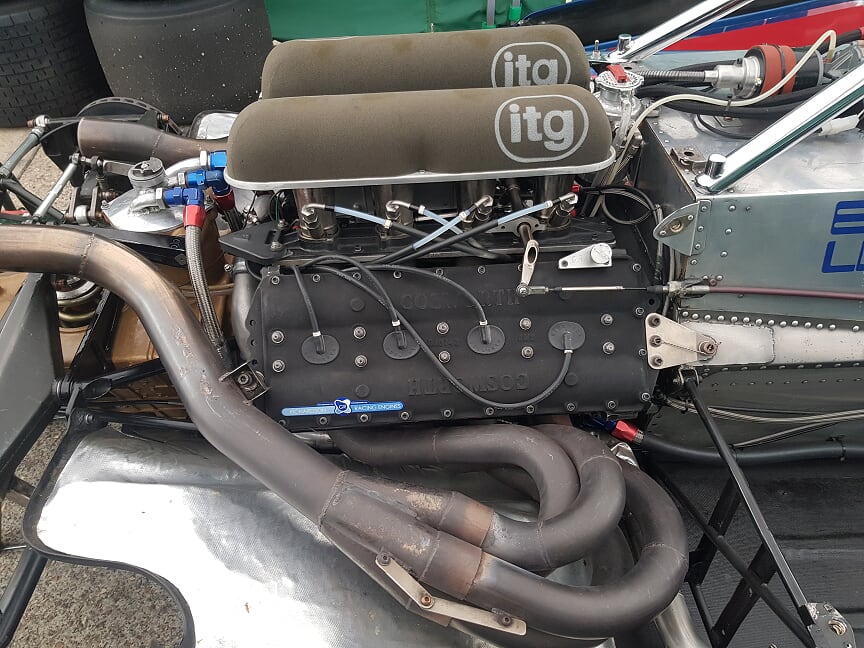

Given the large engine and the relatively open sidepods of the ground effect cars, the installation of these V12s was impressive, with the dozens of inlet trumpets, exhausts, ignition wires and fuel injection pipes, this was perhaps the height of the analogue-era of F1 technology.

At the same time, however, Renault was making progress with its V6 turbo engine, producing even more power than the V12’s. The writing was on the wall for the teams, and they had to switch to smaller turbo engines to stay competitive. By 1983 there were just the turbo engines and Cosworth’s, no other engine maker or format appeared until the banning of turbo engines in 1989.

Ferrari decided to return with an all new V12, having gone from a flat layout to the turbo engine, this was a departure for Ferrari with a narrow 65-degree V angle, keeping the engine slim for aerodynamic reasons. Now producing over 650hp at 13,000rpm, this was the archetypal screamer V12, at full open throttle out of corners it could be clearly heard at the other end of the straight. Despite its advantage on paper, Honda retained their superiority with slightly more power from its wider angle V10. Meanwhile, Lamborghini had arrived in F1 with a V12 engine, the Life team had its brief time with the W12 and Coloni with the Subaru flat-12.

Eventually, the drive for ever greater power lead Honda themselves to switch to the V12 format in order to maintain its competitiveness in 1991 and with it took another championship. The advent of higher quality on board cameras allowed fans to follow Senna on his qualifying laps and watch races onboard, catching the side of the famous yellow helmet and recording the sound just a few inches from the sonorous Honda V12’s +700hp. This added to the legacy of the F1 V12, with Honda having to upgrade to a V12 to beat Ferrari and especially finding a place for the V12 in the hearts of the audience brought to F1 by the Senna-era.

Honda subsequently withdrew from F1 as a result of the global financial crisis, leaving Ferrari racing its much loved V12s. By this time the Ferrari’s 3.5l was running at a heady 16,000rpm and produced an impressive +800hp.

Then, in 1994, when the rules were once again changed, this reducing the engines back down to 3.0l and outlawing the V12 format. Ferrari downsized its V12 for 1995, but the complex era of F1 was underway and again the V12 didn’t fit into these new demands and Ferrari resorted to a V10 for 1996.

In between seasons, Ferrari had hired Michael Schumacher, who came along to test both the outgoing V12 car and the new V10. A curious observation made by Schumacher to John Barnard at the time, was that he preferred the V12. This was less to do with the noise and power, but rather its rotational inertia, as Schumacher found he could steer the car through corners not with power oversteer, but with the spinning mass of the crankshaft inside the engine. This reciprocating mass was heavier with the V12 than with the V10, and he could get the same effect with the lighter newer engine. Of course, this effect only works when turning in one direction, so wasn’t a silver bullet for better handling, but is one rarely talked about and an under exploited area of the V12’s performance.

The last V12 championship had been won in 1991 and the last race win was an emotional one for Ferrari aficionados, with Jean Alesi taking the win at the Canadian GP in 1995. There hasn’t been a V12 engine allowed in the regulations and thus one hasn’t raced in F1 since then.

Reality of the V12

If the V12 won fans over and also gave more power, as that’s what every driver wants to beat their rivals along the straights, then why didn’t the V12 race in the back more than just a few cars at each race over these three decades? The answer is in the cost and the compromises the V12 layout demands.

Looking back to F1 in the late sixties and the newly formed 3.0l regulations, Cosworth appeared with a commercially available engine. The DFV could be ordered by anyone with the money and collected from the Northampton factory, race-ready and just needing a chassis to be fitted into. While the early specification of the DFV produced a little as 465hp, this was a well-developed engine with enough horsepower and plenty of reliability. Teams flocked to it in their droves, this affordable entry to F1 meant complex deals and investment to get a bespoke race engine were not required, the Cosworth engine was a plug and play unit, teams could focus on other things like being clever with the chassis and aero. The popularity of the DFV engine meant that with greater production numbers it became cheaper and used engines came onto the market. What’s more, with most of your rivals racing the same engine, the penalty of having one was reduced, and most teams had the same rear ends, with Cosworth DFVs and a Hewland gearbox.

Given that the clever and agile teams were racing the Cosworth, anyone with some money wanting to beat them would immediately look to having an engine with more power. Its stands to reason, that if can you breeze past your rival on the straights, then the race wins will be yours.

With its engine-lead heritage founded with the V12, Ferrari had always made its own engine, so the V12 format was hardly a question, certainly buying Cosworth’s DFV was out of the question!

With the V12, Ferrari had a power and centre of gravity advantage, but there are compromises with the V12. Developing an F1 engine, even back in the simpler days of the 70’s, was expensive. When you then multiply the complexity of the V12 into the ‘bespoke’ race engine price tag, the cost only rises. Ferrari had the budget and resources, few others did, hence the key reason there have been so few V12s. While there may not have been many F1 V12s, there have been other race engine manufacturers, from major manufacturers (Honda, Renault, BMW) to small companies (Judd, Ilmor), all producing smaller V8s or latterly V10s. This starts to provide the answers to the technical issues with V12s. If they didn’t choose to make a V12 then why not?

As F1 started to become ever more complex and professional from the 70’s through the mid-nineties, the cars have become quicker and the means to make them quicker has become better understood. Given F1 has often raced to a minimum weight, the simple theory that more power means a better power to weight ratio, doesn’t necessarily mean a faster car. As wheelbase, centre of gravity, aerodynamics and fuel consumption are all other factors just as, if not more, influential. With this whole car philosophy, the argument for a V12 soon diminishes, as they could be considered very bad race car engines.

By their very nature, V12 engines are longer and heavier than their V8/V10 rivals. Thus, to meet the minimum weight, there has to be a trade in the weight of the chassis, if indeed the minimum weight can be achieved at all. Many V12 race cars with the heavier engines failed to meet this minimum weight, anything over this limit is a lap time handicap, compounded with other issues from overloaded brakes to added weight in other areas to support the heavier engine.

Then, there’s how the positioning of the major masses along the car’s centreline affect the front to rear weight distribution, with a long and heavier engine at the back, it’s harder to move weight forwards forcing a rearwards weight bias. This being a particular issue when ground effect aerodynamics rewarded more weight over the front axle.

This weight is also having an effect on the car’s rotational inertia, making the car hard to turn with a heavy V12 in the rear. Ferrari went some way to offset this with Mauro Forghieri’s mass-centralised 312T concept, keeping all major masses within the wheelbase and leading to the installation of a transverse gearbox that keeps the gear cluster ahead of the rear axle line, reducing the polar moment of inertia.

Weight continues to be a negative theme for the 12 cylinder race engine, with the engine’s fuel consumption always greater than the V8s. While not an issue with lightly fuelled qualifying laps, this does force the V12 equipped cars to start with a heavier race fuel load or ease off in the later laps, both multiplying the loss of time in the race.

Which brings us to length, remembering that in the three decades of the V12 shorter wheelbases were preferred in F1. The longer engine creates issues for the team to package the chassis, fuel tank, engine and gearbox into a desirable wheelbase. Contrasted to the installed length of the Cosworth DFV which at 50cm was some 30cm shorter than the Ferrari’s flat-12 in the 312T, it meant that the Ferrari was longer than the McLaren M23 it raced against.

With the advent of ground effects, the 70’s style side-mounted fuel tanks became an obstruction to the full length shaped underbody, so the fuel had to be stored between the driver and engine, further exacerbating the greater wheelbase handicap of the V12 engine. Partially to offset this, Ferrari had to run transverse gearboxes, the shorter design of the gearbox being useful to reduce the wheelbase compared to the longitudinal gearboxes run by the DFVs. Also, Ferrari at various points had to wrap some of the fuel tank around the flanks of the monocoque to keep the fuel tank short, thereby having to have fuel stored either side of the driver.

Already the fuel tank has been mentioned as a handicap to aerodynamics, so too was the flat layout of the 180-degree engines of Ferrari and Alfa in the late seventies. Somehow, Ferrari won the 1979 championship with a wing car, albeit with width of the tunnels reduced by the low and wide engine handicapping downforce. Ferrari won that championship with its early season results, but the DFV equipped cars came on strong as the season continued, having a far better engine format to wrap the aerodynamic bodywork around.

Racing an Alfa Romeo flat-12 at the same time, Brabham also suffered an inability to run wide ground effect tunnels for downforce. Their alternative route was the BT46-B fan car, unable to lower air pressure under the car air through a venturi underbody, they chose to suck it out with a fan instead. This was frowned upon by their rivals and the governing body and the fan car was withdrawn from subsequent races, after its sole win in Sweden.

Given that the huge grip benefits of ground effect played against the flat-12 layout, Ferrari and Alfa had to reconsider their engines. Ferrari went the turbo route, while Alfa narrowed their bank angle at the request of the Brabham team. The narrower installed shape moved the cylinder banks and exhausts up out of the way, making room for ground effect tunnels. Matra joined Ligier at this point with a similar narrow angle V12. But the 60-degree V12 had lost its low centre of gravity advantage and remained stuck with its rear biased weight distribution penalty.

It’s worth noting that during the late seventies, both Braham and Liger had been on the rise, winning races with their neat aerodynamic cars fitted with the Cosworth V8. Both teams upward trend ended with the switch to V12 engines, which is a real case for arguing the case that V12 makes a bad race engine.

Additionally, while Ferrari’s 12 cylinder was always a largely reliable engine, Matra and Alfa could not make the same argument, the cost and complexity of the engine lead to less development and a short tenure at each team.

By 1983, teams either ran turbos or the Cosworth, although Osella ran the Alfa Romeo V12 more out of commercial necessity than performance.

With the ban on turbos and reintroduction of big normally-aspirated engines, Ferrari opted for the 12 cylinder again. But their opposition chose V8s and the new-to-F1 V10 layout. Each had advantages over the V12 in weight, packaging and fuel consumption, with only a small power deficit. Soon, the sport’s designers realised that the V10 was the ideal format within a whole-car philosophy, less compromises leading to faster laptimes.

Ferrari during this period was extremely innovative with the packaging the V12, the 640 chassis and its successors were a tour de force of new ideas, the semi-automatic gearbox and lightweight structures. But these were of avail when the teams with the smaller lighter engines could follow suit and offset the V12’s decreasing power advantage.

As Ferrari pushed the V12 during this period, reliability suffered and the team’s performance fell behind the dominant McLaren Honda team. Honda proved the exception to the rule with the MP4-6 and the Honda V12. Within the realms of whole-car performance, Honda and Ferrari lead the field with their powerplants and organisation, less so with their chassis performance. Below them were a series of teams working hard with aero and suspension technology, but with less engine power from V8s and V10s. The scales were about to shift, but for Honda and its meticulous approach to its F1 programme at the time, had one more shot at the championship, slugging it out with Williams in 1991, as Ferrari declined. With the power and reliability advantage, McLaren won. But the sophisticated chassis of the Williams, allied to the rounded Renault V10 showed its potential and in 1992 this reversed the scales, and the V12 McLaren Honda lost out and only narrowly beat Benetton, with of all things a Cosworth V8!

As the new 3.0l era run out to the current Hybrid power unit regulations, the V10 became the preferred engine format until it was outlawed and the V8 format was regulated.

For many, the V10 is a divisive format, not a classic V8 which is honoured in so many countries as the ideal engine format, nor as romantic as the V12. But the V10, as odd as it stands in the engine development world, produced a huge amount of power and noise. The tone out of the exhausts deeper and more bellowing than the latter V8s with their higher RPM. During the final years of the normally-aspirated era, the red lines of the engine rose, eventually ending with the dizzying 20k rpm of the final Cosworth engines.

Good or bad?

For all the dewy-eyed reminiscing, it’s clear the V12 has a chequered history in F1, a lot of it bad and there was never a golden V12 era. To laud them requires a rose tinted visor, but yet they had that certain something.

Engines are both a technical and emotive subject, its hard to reach a firm conclusion on whether Vettel said, “bring back F***ing V12s” or should have said “F***ing V12s”. It depends on who is asking the question. For the engineer they are not great race car engines, too large and too fuel thirsty to make a car fast around a lap or throughout a race. For the fans they make a great noise and for the drivers they make a lot of horsepower.

Modern society can frown upon excessive consumption, it can be argued that’s exactly what F1 is all about. So, the V12 could be seen a black mark in a politically correct world, certainly compared to the clean and efficient hybrid engines, or (whisper it) fully electric power trains.

Do V12s belong back in F1? It depends whether the sport wants to cater for the legacy fans or want to change perceptions for a new era of fans?