As the confetti blows away from the podium at Le Mans after the conclusion of the 2019 24-hour race and the 2018-2019 super season, the future of the race and the blue riband cars that might win it have been agreed.

For 2021 there will be new rules, effectively ending the LMP1 category and replacing it with a new Hypercar format. With this, companies such as Aston Martin, with the Red Bull designed Valkyrie supercar, can enter Le Mans with a modified version of their road going car and go for top honours. There will no doubt be other contenders, bringing exciting cars to La Sarthe in the future. And there’s also the opportunity for a prestigious triple crown victory for the winning designer.

Current LMP regulations

The Blue Riband class at Le Mans has varied over the years, split between road cars and prototypes, with numerous variations in between. The current top class is LMP1 (Le Mans Prototype 1), which is in fact split into two, a premier category LMP1H for manufacturer entered Hybrid cars and a lower class for privateer cars without hybrid powertrains. Although LMP1H was solely represented by Toyota this season, it has recently seen Audi, Porsche, Bentley, Nissan and Peugeot enter. With Le Mans being the jewel in the crown, the current rules and entry to the 24-hour race are run by the FIA’s World Endurance Championship (WEC).

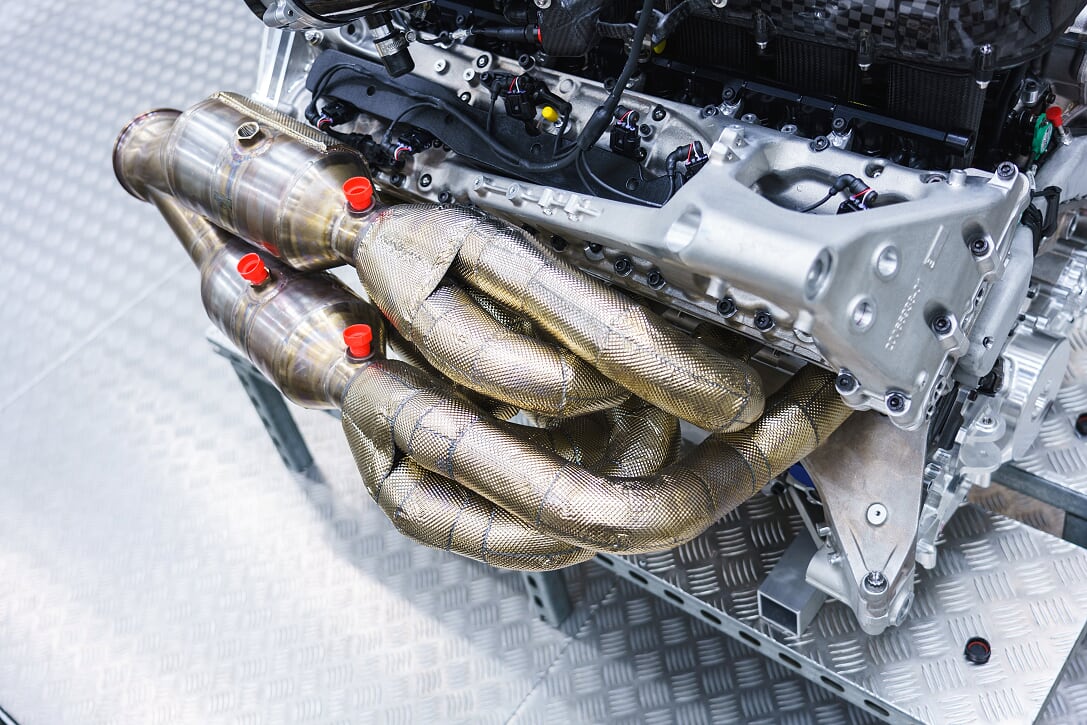

LMP1H is a prototype category, thus the cars are unique. There is no demand to represent any aspect of the entrant’s road cars, even the old legacy rules to carry spare tyres and luggage are no longer in the ruleset. Therefore, the current LMP1H is a thoroughbred race car, with 1000hp delivered through a hybrid 4WD powertrain, complete with complex aerodynamics, suspension and electronics to match. To see an LMP1 stripped of its outer bodywork, it’s clear these cars are near to F1 levels of technology and complexity.

Despite the success of the category to encourage major manufacturers to enter, there has been a drift away from the championship by the tier1 car companies, enticed by other categories, in particular Formula E, despite the LMP1H hybrid road car link.

Costs appear to be a factor, with a Formula E entry being far more cost effective than a full entry to WEC. There’s clearly more to their decisions than merely costs, such as rival manufacturers, relevant technology, marketing and exposure. All these factors have led to a new set of WEC rules to introduce new entrants and a more exciting car format.

What has been termed the ‘Hypercar rules’ will come into effect for the 2021 season, leaving Toyota the sole Entrant for the last LMP1H season in 2020. These new rules are underpinned by three aims; parity between the competitors, fixed budget and exciting looking cars.

While this is known as the Hypercar category, there is flexibility in the rules split between the race-prepared roadgoing supercars and also a prototype race car in the style of a Hypercar. So, it’s not inevitable that the class will be won by a recognised manufacturer’s supercar (of which 20 must be manufactured), but a restyled race car. This latter restyled race car approach has worked with great success in the American Daytona Prototype series (Dpi).

Either way, both will be required to meet the technical regulations by producing 750hp and weighing no more than 1100kg, while running on spec tyres. The horsepower cap can be met either with an internal combustion engine (ICE) or a hybrid ICE\Electric with no more than 270hp (200kw) from the ERS. Specific caps are placed on the ICE with fuel flow restrictions used to cap the horsepower, a road car based entry must use the car’s production engine, while the prototype has a free choice or a bespoke or production engine. Likewise, with the hybrid system, Hypercars must use the same layout as the road car and the prototypes must use a front mounted MGU set up.

Another area where there is greater freedom is in the aerodynamics. This is partly to accommodate the road car stylists’ ideas and to provide greater scope for the prototypes to look different from one another. This freedom extends to the underfloor, where the ground effect tunnels are also free. Any internet search of Le Mans crashes will inevitably show up flip over accidents, which were caused by aerodynamics and, in particular, the large flat underfloor of the prototype cars of the time. Subsequent Research and Development has reduced the tendency of these long cars to flip over at high speed. There remains a question as to how will this tendency be controlled without underbody restrictions? One aero safety feature is the sharkfin, developed by Lola to reduce the chance of a car flipping when in a slide, and it’s likely this will be one of the aero-safety criteria enforced within the new rules.

This greater technical freedom and split base-car approach could potentially lead to inequity between the competitors, but the FIA already have a solution to bring fairness to a series with such a varied field of entries. Balance of Performance (BoP) is a system already in place in the GTE class, this helps to regulate the performance of different road cars to the same predicted lap time. The BoP process works from when the competitor first approaches the FIA to enter the class. Open technical interchange between the two uses simulations based on real technical data to predict the cars performance. This iterative process sees the FIA set performance limitations on the entrant to achieve parity with its rivals based a target lap time. BoP goes further and continues when the cars are homologated and start racing, any advantage seen in reality and not in the simulations is offset with further technical restrictions. While this is not a perfect system, and teams with any perceived advantage can be capped, overall BoP works well to get a varied field running in one competitive class. Thus, BoP will be applied to the Hypercar rules, to ensure one entrant doesn’t run away with a huge advantage, due to the car its based upon.

With the power to weight calculated and BoP setting the baseline performance for the category, the Hypercars are intended to lap Le Mans at 3m30s, which is on par with the current LMP2 class and will not ensure that the Hypercars are a dead cert for an outright win, although the pit allowances for fuel and tyres may also sway the result, as much as lap time after 24 hours of racing. On shorter length and duration races in other rounds of the WEC, the LMP2 cars may even win on performance alone.

So far, only Aston Martin and Toyota have confirmed their intent to enter the category. Looking at the potential for road gong based Hypercars, McLaren, Ferrari and even Mercedes have projects ongoing that could meet the rules. While the prototypes entering the category could include the likes of Dallara, Ginetta and ByKolles. Thankfully, there shouldn’t be a lack of entries to the category.